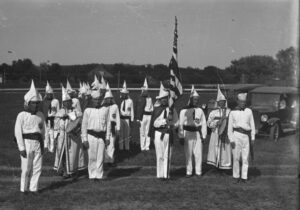

Ku Klux Klan members carry an American flag in a parade in Gering, NE, ca.1920s. RG4909-1-29

By Kylie Kinley, Assistant Editor

July 4, 1924, saw the start of a three week cross-burning frenzy in the Nebraska Panhandle. The next day the Scottsbluff Star Herald reported that American independence had been celebrated “by the blazing of fiery crosses of the Ku Klux Klan at many points in the valley.” The first cross that burned on July 4, 1924, “was a mere ‘curtain raiser’ being only 4×8 feet in size made of iron pipe, which had been wrapped with oily rags.” Four more crosses burned in Bridgeport that night, the largest a “monster cross” 35 feet high and 25 feet across. The Klan also burned a cross in Bayard, and another with a “blood red tinge and great height” was identified in Scottsbluff. The Klan used the Scottsbluff site to burn a second cross on July 8, and also burned a cross south of Haig with “the emblem of the invisible empire being plainly distinguishable from many points in the valley,” the July 15 Star-Herald reported.

Nebraskans are familiar with the Klan’s horrendous acts of violence and bigotry, but many don’t know that Klan members cloaked their actions not only with white robes and masks, but also with patriotism. Nebraska Klan membership peaked at an astonishing 45,000 members in the mid-1920s. The KKK that came to Nebraska in 1921 was actually the second organization by that name. Anti-civil rights Southerners established the original Klan during Reconstruction, using terrorism to deny African Americans voting rights and other basic civil and human rights. To limit the Klan’s power, Congress passed The Ku Klux Act or Force Laws of 1871, which empowered the President to combat the KKK and other white supremacy organizations.

The second Klan movement began in 1915 in Atlanta as a renewed effort to limit African Americans’ access to better employment, education, and standards of living. Industrialization created new opportunities for African Americans, and white supremacists were determined to limit those opportunities. But the new Klan wasn’t just an anti-black organization, nor was it primarily Southern. The re-birth of the Klan was a reaction to large numbers of non-northern European immigrants. The Klan was no longer merely anti-African-American, but also anti-immigration, anti-Semitism, and anti-Catholicism.

Nebraska’s African American population increased by more than 70 percent between 1910 and 1920, and “by 1920 Omaha’s population of 191,601 included 10,315 blacks; Lincoln, population 54,948, had 896 blacks. Grand Island had 126; Hastings, 81; and North Platte, 59.” (Schuyler, 243). The Klan flourished in these communities—but also in many towns with no significant black population.

But while cross burning is usually associated with intimidation or as a calling card for violence, the July 1924 North Platte Valley cross burnings were the Klan’s attempt to advertise an upcoming rally. They took out ads in the newspapers, too, but burning crosses earned them free publicity through extensive newspaper coverage. The rally was held July 14. The following day’s Star Herald headline read: “Ku Klux Klan Holds Big Meet Last Night – Estimated That 2500 Men Visited Brown Canon Where Coweled Sentries Guarded Gates to Invisible Empire to Hear Lecturer.”

According to the report, the lecture focused almost exclusively on “Americanism” and “patriotism”: “Old Glory proudly floated from the flagstaff in the center, the stars and stripes waving brightly in the glaze of the spotlights from several cars closely packed, extending two miles along the highway, waiting to gain admission to the gathering…With the first fiery cross burning high on the side to the east of the meeting, the Klansmen with the aid of colored flares, formed a living, blazing cross on the side below.” Even the report’s imagery — Old Glory proudly floating in the glaze of spotlights — seems to echo the national anthem’s broad stripes and bright stars streaming in the rocket’s red glare. But instead of dawn’s early light, a “living, blazing cross” gave proof that the flag was still there.

The speaker, KKK principal lecturer Dr. C. Arnold Stewart,

“opened his remarks with the statement that he was proud he was an American citizen; that any man or woman who was not proud of that fact had no right here and should not have a home in this country. This American nation has been accused by those across the seas of being a boastful nation, and we are, he declared, because we have something to boast about. He repeated that he was proud of the fact that he was a citizen of the Invisible Empire, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. He remarked that everyone present would undoubtedly applaud his statement regarding American citizenship while not many at that time would applaud his statement regarding the Klan. It was his purpose by means of his lecture to convince those present that it was a thing of which to be proud. All that American citizens need to do is to get their eyes open to a few things and they will feel differently regarding the Klan.”

Stewart’s tone and theme, if not his exact words, would be at home on the Internet. “I bet people you will just scroll past this…” or, “Anyone who doesn’t agree with XYZ shouldn’t live in America…share if you agree!” are common rallying cries for different agendas, many of them claiming patriotism.

Several hooded Ku Klux Klan members follow a hearse in a funeral procession in Chadron, NE, in 1926. RG5832-1

Stewart’s words were echoed a year later after the Klan held its first public demonstration in Chadron in 1925. The Chadron Journal reported on August 28 that Klan officers insisted that the Klan was “not an ANTI organization but a PRO organization believing in patriotic, protestant Americanism, as their floats and banners portrayed.”

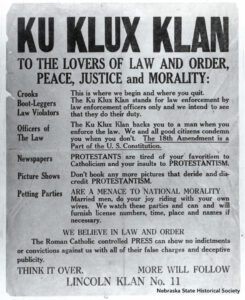

Four years earlier, “King Kleagle” Edward Young Clarke told the Omaha World-Herald that “We are an organization of Americans. We are non-everything that is un-American… We are a secret organization of Protestant, white, gentile Americans, ready to uphold the constitution” (Sept 11, 1921).

The hypocrisy of stating that one’s group is “PRO” while in the same breath excluding Jews, Catholics, and non-whites seems to have been lost on the klansmen. The Klan’s ad in The Gering Courier on October, 17, 1924, made their “pro” sentiments more clear: “Are You a Native Born American Citizen? Are You a Protestant? Are you a Gentile? If you can qualify with the above requirements you are invited to bring your wife and hear a lecture on the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in this valley by a National lecturer for the organization on the night of October 28th.”

This ad assumed that the reader was male, but women could also be active in the Klan. Around 2,000 women attended the regional Klan convention in 1925 in Kansas City. Part of the convention’s entertainment included watching 30 girls in khaki uniforms execute drills around a mammoth electric cross and an American flag (Schuyler, 233). Such demonstrations publicly asserted the Klan’s commitment to “patriotism” even if the group’s terrorism happened at night and under robes. Women were also part of the Nebraska Klan. The Hastings Klavern held a parade in September 1926 that included 500 robed participants, “some of them women’s groups, marching in cross-formations” (Creigh, 707).

Ku Klux Klan rally in Neligh, NE, circa 1928. RG2836-002256

The Hastings Klavern was popular from their first gathering in 1923. Between 3,500 and 4,000 people gathered at Prospect Park on a Sunday afternoon in September 1924 to hear about the Klan’s purposes. In July 1925, 25,000 visitors came to see the Imperial Wizard at a district meeting. African American and Jewish populations were small in Hastings, so “much of the hate-activities of the Klan were directed against Catholics. Word-of-mouth sources tell of fiery crosses blazing from time-to-time on lawns of local Catholics and in the countryside, and of terrorism directed toward some businessmen who did not join or otherwise support Klan activities” (Creigh, 708).

Cross burnings, parades, and popular speakers were part of Klan gatherings throughout Nebraska in the 1920s. According to historian Jim McKee, “In 1921, the first Nebraska Klavern opened in Omaha with an agenda of expanding the anti-black plank to include Roman Catholics and all immigrants. That year, the KKK claimed over 1,000 members in Nebraska, 45,000 the following year and 4 million nationally by 1925.”

But while the Klan was incredibly popular in Nebraska and other northern states, other Nebraskans worked tirelessly to limit the Klan’s growth. One influential Klan opponent was Chancellor Samuel Avery of the University of Nebraska. After the Lincoln Star reported in 1921 that the Klan had held an initiation ceremony on campus, Avery cited a university senate rule banning secret organizations and promised that any student who joined the Klan would be suspended. “The university should be characterized by a broad liberal spirit of fellowship,” he said. “Learning knows no distinction or race or color” (Schuyler 246).

While students were banned from joining secret organizations, Lincoln’s Klavern No. 11 was still very popular. The July 2, 1924, Lincoln Star reported that 25,000 to 30,000 watched the Klan’s fireworks display, and 1,100 white-robed klansmen marched in a parade earlier in the day. Some of the signs read “Long Live the Little Red School House,” “One Flag,” and “Emblem of Americanism.”

“Americanism” was a popular topic for rallies. On July 25, 1924, in McCook, a crowd of 10,000 people watched a parade of 200 klansmen and listened to a lecture on “Americanism.” A prayer from a klansman in a McCook church was recorded in part: “Give us to know that the crowning glory of a klansman is to serve… keep ablaze in each klansman’s heart the sacred fire of a devoted patriotism to our country and its government. And Oh God, give us men” (Schuyler 239).

KKK Poster from Lincoln Klavern No. 11, circa 1928. RG2124

In 1925 a Klan organizer from Atlanta drew more than a thousand people to the city park in Curtis, Nebraska, where he warned that “foreign elements” would soon inundate Nebraska. Later that year, Hiram Wesley Evans, imperial wizard of the Klan, made appearances in Omaha, Lincoln, York, Hastings, North Platte, and Sidney. He said Nebraska had an ample amount of “genuine Americans” and concluded, “It is good to know that the West is not being undermined as the eastern section of the nation by un-American elements.” He criticized the “immodesty of dress” of American women, the “unwarranted predilection for foreign art,” and “high taxes.” Evans also encouraged listeners to make the Klan into a “dependable agency for the achievement of civic righteousness.” (Schuyler 237)

Civic righteousness, patriotism, Americanism, and “the little red school house” of American education are all topics Nebraskans still talk about today. More interesting, then, is the way promoters of bigotry, hate, and racism used these topics to hide their ideas in the same way that they used white robes to hide their faces. While many Klan members in Nebraska did not keep their affiliation a secret, the book Adams County: The Story relates that klansmen in Hastings tried to protect their identities (707). During one parade, the local cobbler named A.J. Sousa stood on the side of the street and watched the klansmen’s feet, identifying his customers by their shoes and revealing them as klansmen. This connects to another important Nebraskan tradition that is etched above our state capitol’s steps. It embodies a sense of patriotism unlike the adulterated patriotism of the Klan. The inscription reads: “The salvation of the state is the watchfulness of the citizens.” Sometimes that salvation happens from the small act of identifying feet.

Sources

Creigh, Dorothy Walter. Adams County: The Story. Hastings, Neb.: Adams County – Hastings Centennial Commission, 1972. Print.

The Chadron Journal. “Klan Stages Big Parade in Chadron.” 28 Aug. 1925. p. 1. Print.

The Gering Courier. “Ku Klux Klan is Now in Our Midst.” 4 July 1924. p. 1. Print.

The Gering Courier. “Knights of the Ku Klux Klan Advertisement.” 17 Oct. 1924. p. 5. Print.

The Lincoln Star. “Klan Spectacle Draws Big Crowd.” 2 July 1924. p. 4. Print. The Omaha World Herald. “Great Klan Ceremony is Planned in Omaha.” September 11, 1921 p. 8 col 1. Print.

The Scottsbluff Star Herald. “Kluxers Burn Fiery Cross in Valley Towns, Bridgeport Scene of Big Demonstration.” 5 July 1924. p. 1. Print.

The Scottsbluff Star Herald.”KuKlux Klan Holds Big Meet last Night.” 15 July 1924. p. 1. Print.