This article appears in the Winter 2024 issue of Nebraska History Magazine. Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of the magazine per year. The entire article is below. A PDF of the magazine layout with additional photos is here.

By Leo Adam Biga

Nebraska feature filmmakers are a rare breed. Director Fred Niblo flourished in the silent era. Producer Darryl Zanuck ruled as a Hollywood Golden Age mogul. Writer-director Alexander Payne owns two Academy Awards and his films have been nominated for many more. Jon Bokenkamp is the creator of The Blacklist.

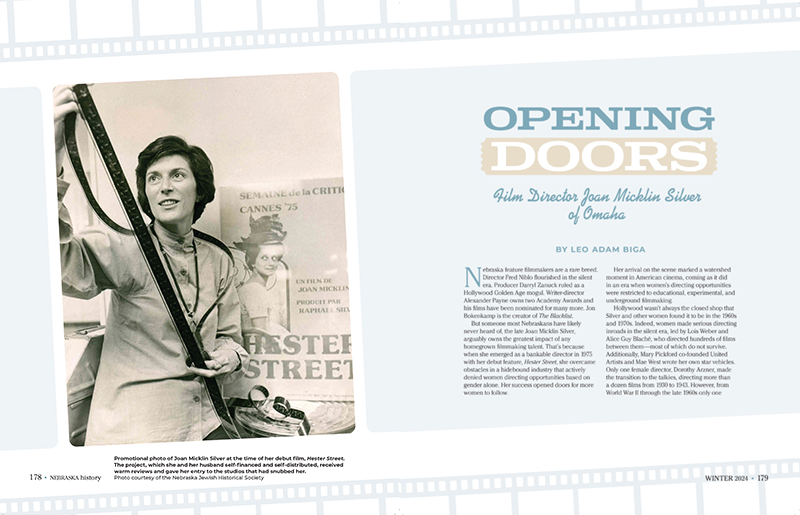

But someone most Nebraskans have likely never heard of, the late Joan Micklin Silver, arguably owns the greatest impact of any homegrown filmmaking talent. That’s because when she emerged as a bankable director in 1975 with her debut feature, Hester Street, she overcame obstacles in a hidebound industry that actively denied women directing opportunities based on gender alone. Her success opened doors for more women to follow.

Her arrival on the scene marked a watershed moment in American cinema, coming as it did in an era when women’s directing opportunities were restricted to educational, experimental, and underground filmmaking.

Hollywood wasn’t always the closed shop that Silver and other women found it to be in the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, women made serious directing inroads in the silent era, led by Lois Weber and Alice Guy Blaché, who directed hundreds of films between them – most of which do not survive. Additionally, Mary Pickford co-founded United Artists and Mae West wrote her own star vehicles. Only one female director, Dorothy Arzner, made the transition to the talkies, directing more than a dozen films from 1930 to 1943. However, from World War II through the late 1960s only one woman directed any Hollywood features, actress Ida Lupino, who enjoyed a short but fruitful directing career. A few female indie directors made waves, primarily Ruth Orkin (she co-directed with her husband Morris Engle) in the 1950s, followed in the ’60s-early ’70s by Shirley Clarke, Juleen Compton, Barbara Loden, and Stephanie Rothman. But their work was little seen outside the art house circuit. Women were absent from a studio directorial chair except for Lupino’s last feature directorial effort in 1966, The Trouble with Angels.

Why did women get cut out of the system so completely that directing became, by any practical measure, the de facto or exclusive province of men? Male privilege, patriarchy, and patronage explain much of it. Once the movies became a lucrative industry, men consolidated control of the financing and production, just as they controlled all American industries. Because directors held power, the men running the studios confined and conferred that power to other men and rarely, and then only grudgingly and sparingly, gave it to women.

Similarly, Hollywood made it impossible for men of color to break through as directors in the mainstream industry until the 1970s. It took another decade or two before Black directors became a real force (Spike Lee, Carl Franklin, John Singleton, Antoine Fuqua).

Like their black male counterparts, women’s absence from directing had nothing to do with talent and everything to do with access. Despite steep barriers to entry, Silver persevered and would not be denied.

Comic turned director Elaine May signaled the return of women directors with A New Leaf in 1971, along with Loden’s Wanda that same year, Karen Arthur’s Legacy in 1974, and Silver’s Hester Street the following year. Silver also collaborated with Loden on the ’75 short, The Frontier Experience when Loden, who starred in the piece, directed Silver’s script. Of those artists, only Silver enjoyed anything like a sustained directing career.

Silver and other women wanting to direct took advantage of the dismantling of the old studio contract system around the same time New Hollywood hot shots from television and film schools supplanted the old guard. The work of directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin, and Steven Spielberg seemed to connect more with audiences. If these new male voices and visionaries could reach audiences, then why not women?

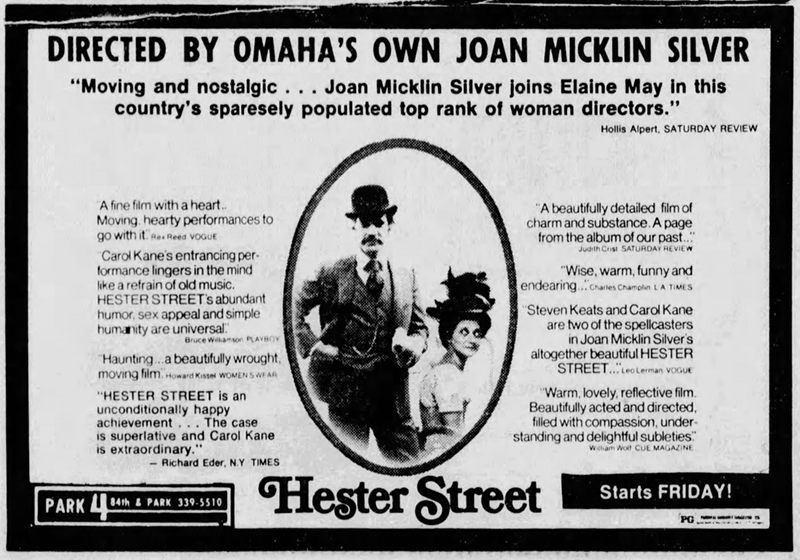

Silver proved her chops with Hester Street. The low-budget independent project was passed on by Hollywood, but it got the industry’s attention by earning more than a dozen times its cost, garnering strong reviews and netting award nominations. That success paved the way for Silver to work in the mainstream industry, though not right away. Still, it was Hester Street that eventually gained her entry to Hollywood’s Old Boys Club.

Veteran Columbia University film professor and noted indie film producer, marketer, distributor, and champion Ira Deutchman, handled Hester Street’s non-theatrical bookings while working for Cinema 5. He remained close to Joan and her producer-partner husband, Ray Silver. Deutchman said Hester Street energized the then-fledgling American independent film movement.

“Yeah, it definitely did. It was inspirational as a kind of landmark independent success but also it was about the fact Joan was a female director. There was no other story like that, at least within those couple of decades, about a woman being able to make the movie she wanted to make. There was a mini-boom of female-directed independent films that happened right after Hester Street. There’s no doubt the success of that film got others interested in the fact there was this un-mined talent out there that could be taken advantage of.”

He credits Hester Street with shaping his own appreciation for what indie films could do.

“I was definitely inspired by the success of the movie. The Cinema 5 offices were around the corner from the Plaza Theatre, where the film originally opened. And every day going to and from work I would see these lines down the block of people trying to get into Hester Street. It really imprinted itself on my brain.”

Four decades after its original release Hester Street is getting a second life thanks to a new stage adaptation that made its world premiere at the prestigious Theatre J in Washington DC last spring. Deutchman is a co-producer of this play with music. There’s hope it will go to Broadway. Restorations of the film that inspired the play, along with other Silver films, are getting screened around the country due to Deutchman’s mission to have her work preserved and her legacy celebrated.

“It’s all about bringing Joan back to the surface again,” he said. “Even before the play I was working with Joan. All of the rights of her films were either expired and were about to expire with the various distributors.”

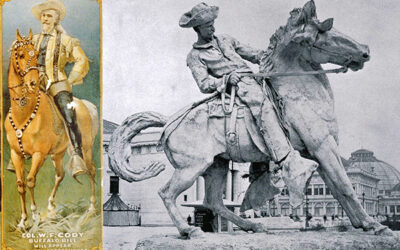

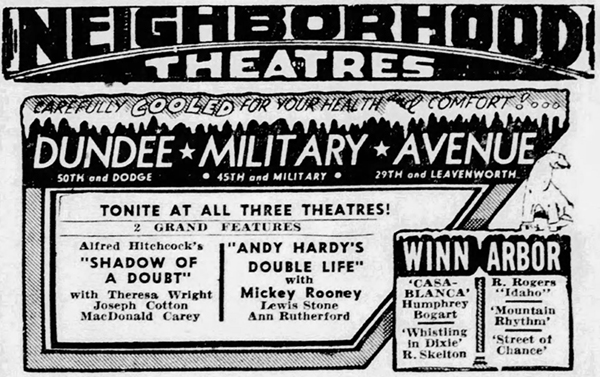

Silver frequented the Dundee Theatre growing up and often cited Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt as an influence. Omaha World-Herald, July 10, 1943.

Close to Home

Making Hester Street so enduring is how personal it was to Silver. She directed several films that spoke to her family’s Jewish immigrant experience but this one spoke directly to her heritage in ways the others didn’t.

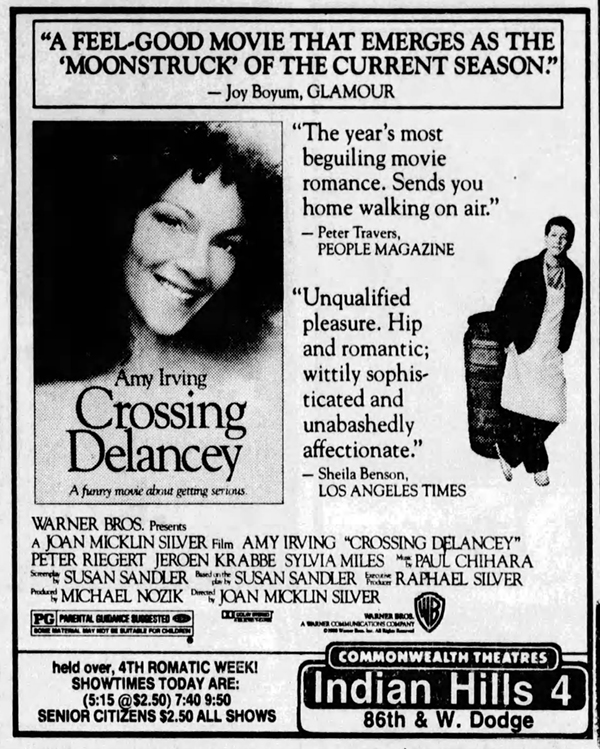

The film explores the emancipation of a young immigrant woman from her husband’s flippant, philandering ways within the tableaux of Lower East Side Jewish emigres at the turn of the twentieth century. She made a bookend piece in Crossing Delancey (1988), a contemporary romantic comedy which looks at the dating rituals and courtship mores of descendants of Lower East Side elders and ancestors whose immigrant spirit paved the way for their twentieth century comfort.

The contours of her own family’s immigrant experience made quite an impression on Silver. Her father Morris founded Micklin Lumber Company. Joan said her father, who was twelve when he and his family arrived from Russia, “had very distinct memories of coming over and what it was like to be young, excited and terrified at having to learn a new language in a strange country… and he told those stories very vividly.”

Her mother, who was only a toddler when she arrived, had no recollection of the experience, but her older siblings did and Joan’s uncles and aunts shared their memories with her during visits to the family’s Yiddish-flavored home.

“So many families don’t want to talk about the experience of immigration,” Silver said. “It’s traumatic. They want to become Americans as soon as possible and they want to leave it all behind them. But my family was of the other variety – that loved to tell the tales. I was always fascinated by all the stories they told. Of the people that made it. The people that didn’t. The people that went crazy. The people that went back. I remember sitting around the dinner table and hearing stories that were very funny and enjoyable and strong and interesting and serious. So I was attracted to those stories in the first place. My father was ill during my teenage years and he was home a great deal, so I spent a lot of time with him. He was looking for somebody to talk to and believe me I was there and I was really happy to talk to him. I’ve always thought immigrants fall into two experiences: those who don’t want to talk about it at all and those who want to talk about it all the time and that was my father – he loved reminiscing about it. As a very bright, questioning man, he was also interested in the world, politics, current events, and books. I was so lucky to have talk after talk with such a wonderful father at a time when it was unusual for fathers to talk to their daughters.”

An Omaha Central High School graduate (1952) who frequented the Dundee Theatre growing up and often cited Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt as an influence, Silver held close the legacy of her elders having escaped Russia for the United States and establishing a generational family business.

The idea of transforming oneself without losing one’s identity is something Silver could readily relate to. “I’ve always loved film very much, and I wanted to make it in that field. I wanted to direct, but I didn’t want to be a man. I wanted to be a woman. I wanted to be myself,” she said.

Although her films were not exclusively Jewish-themed, she often explored her heritage on film, inspired by her family’s stories. Her immersion in those tales not only gave her background for her first feature, but an earlier directorial effort, the documentary short, The Immigrant Experience: The Long Long Journey (1972). In researching it, she came across the Abraham Cahan novella, Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto, that she based Hester Street on. She went on to direct the National Public Radio series Great Jewish Stories from Eastern Europe and Beyond. She revisited the Lower East Side to explore the intersection of old and new Jewish life in Crossing Delancey.

In 1995 the National Foundation for Jewish Culture (NFJC) honored Silver with a Jewish Cultural Achievement Award in the media arts category, which she accepted in memory of her parents. Her fellow honorees included Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Arthur Miller.

Referring to Silver’s work, NFJC executive director Richard Siegel said, “In Hester Street and Crossing Delancey in particular she does something that very few other filmmakers have done, which is to look at the American-Jewish experience in some depth and with considerable insight, from the inside, as it were.”

In her acceptance speech the filmmaker explained how someone from such a goy hometown “could become so addicted to Jewish stories and characters.” She referred, of course, to the stories her family told “…dotted with a pungent Yiddish and much laughter at the human comedy of it all. Such were my introductions to the magnificent and terrifying history of the Jews. When I began making movies I was inevitably drawn to stories which had so much emotional weight for me as I grew up.” But, she added, “making movies about the Jewish experience is a dangerous prospect. Every other Jew has an opinion. You can never satisfy everyone. I learned this after an early screening of Hester Street.”

Silver continued exploring Jewish themes. In the 1997 Showtime movie, In the Presence of Mine Enemies, she directed a Rod Serling script originally produced live on Playhouse 90. Her film of the script starred Armin Mueller-Stahl as a rabbi trying to hold his community and family together in the Warsaw ghetto of World War II. Mine Enemies marked the first time she dealt overtly with the Holocaust in her work.

Her final feature, A Fish in the Bathtub, starring the real-life husband-wife comedy team of Jerry Stiller and Ann Meara, completed Silver’s unofficial trilogy of Jewish American-themed stories that began with Hester Street and Crossing Delancey.

She returned to her interest in immigrant tales with a doc project, The Bagel: An Immigrant’s Story, which she embarked on with food writer Matthew Goodman, author of Jewish Food: The World at Table. In their research the pair found the bagel has strong reverberations with the greater immigrant story in America and the assimilation and discrimination that’s part of it. “It came from Poland, it struggled and strained and went through everything most other immigrants do before it prospered,” Silver said. “That caught my imagination so totally when we figured that out that we decided, Okay, let’s do this.”

Memories of favorite foods, especially aromas, are known to be among the strongest our brains store. As the bagel is a food bound up in ritual, whether along family ethnic lines or urban lifestyle lines or breakfast staple lines, it is a food that serves as a nostalgic “touchstone,” Silver said.

“People think about it and it’s sort of like Proust’s (Marcel) madeleines. It has kind of ringing memories for people.” Her own remembrances of things past take her back to when she was a little girl and her father brought her to a downtown Omaha bakery for “the best rye bread you can imagine and wonderful bagels.”

The doc was unfinished at the time of her death in 2020 though all principal photography was complete. Her grandchild Jack, who grew up watching movies with Joan and Ray, has the wealth of footage left by Joan and he’s seeking funding to complete the film in her honor.

Breaking In

Fascinated by the tales her family shared and that Hollywood dream merchants told, Silver was an avid reader from a young age and early on showed a knack for storytelling herself at Temple Israel Synagogue and Central, writing sketches for school plays. Her departure from Omaha, at age seventeen, to attend Sarah Lawrence College in New York State occurred right around the time her father died. Later, she met Ray Silver, married, and moved with him to Cleveland, Ohio, where he worked in real estate. She bore three daughters and, in between raising a family, haunted cinemas and began writing for local theater.

Excited by what was happening in film in the late ’50s-early ’60s with Italian Neo-realism, the French New Wave, and American independents like John Cassavetes and Clarke, Silver yearned to be part of that vital scene. But Cleveland offered little hope for launching a project. Then fate intervened. At a party she met Joan Ganz Cooney, a founder of the Children’s Television Workshop, who put her in touch with Linda Gottlieb, then an executive with the Learning Corporation of America. Gottlieb fed her freelance scriptwriting work and when Silver announced she wanted to direct as well, she got her wish with that string of short educational films, including The Frontier Experience, some of which aired on public television and were otherwise screened in schools, community centers, and film clubs.

The very idea of a woman directing in Hollywood was anathema to the men who ran things. Women as directors were an afterthought or aberration for studio and network heads and executive producers who either forgot, didn’t know, or didn’t care that women were once embraced as directors. Changing the status quo would take time.

With the educational and short film markets offering two of the few directing routes open to women, Silver gladly worked in that arena to gain professional experience and credits. She never lost sight, however, of her ultimate ambition of directing feature films.

Between Long Long Journey and Frontier Experience, Silver, with Gotlieb as producer, made two well-regarded but rarely screened LCA shorts, The Fur Coat Club (1973) and The Case of the Elevator Duck (1974), which both lovingly feature New York, whose energy and diversity she loved. The films show a knack for framing, locations, and working and eliciting honest performances, in these cases from non-actors. Fur Coat Club starred Silver’s then-nine-year-old daughter Claudia and her real-life friend Emily Chase.

Minus any dialogue, Fur Coat Club chronicles Claudia and Emily’s urban adventures in a friendly competition to see who can touch the most fur. Gordon said the film “hints at some of Silver’s socially progressive ideals,” as when “Claudia rubs up against the back of what she presumes is another white woman in a fur coat bending over a drinking fountain in the park,” only “it turns out to be a Black man.” “Looking down at her in a low angle shot from Claudia’s perspective,” Gordon wrote, “the man smiles warmly. Claudia smiles back and then goes in for some non-furtive extra fur rubs before the two low five and she goes on her way in search of her next feel. When the police arrive at the fur shop, a Black officer is the one who gently interacts with the girls. These might seem like insignificant moments, but they were certainly intentional and important in their small way: at a time when school integration was still being debated and when social and racial unrest was peaking, such easy moments of easy interracial interaction were normalizing.”

In that same spirit, Silver centered Elevator Duck on a Black youth, Gilbert (Robert Lee Grant), in a NYC housing project whom, Gordon wrote, “fancies himself an undercover detective.”

Gordon noted that Silver was inspired to make the films “by contemporary stories featuring mischievous, irreverent, and adventurous kids,” including Louis Fitzhugh’s young adult novel Harriet the Spy and the movie The World of Henry Orient. “Fur Coat Club also had personal roots,” Gordon wrote, with its plot “inspired by Claudia’s real-life fur coat club, a game she invented with her best friend.”

Documentaries and narrative short films were Silver’s own training ground and helps explain why her feature work has such a sense of verisimilitude to it. When Silver decided to pursue feature filmmaking, she and Gottlieb formed their own production company. With Joan’s properties lying dormant and no directing jobs in the offing, she despaired. Then a story of hers based on interviews she conducted with wives of American POWs and MIAs was serialized by McCall’s magazine. Universal Pictures optioned it. Veteran Hollywood director Mark Robson became attached to the property. She got released from the project when she dared to question his take on the story. James Bridges was brought on to realize the script and he and Silver shared screen credit for Limbo (1972). Though unhappy with how her material was interpreted, she got the equivalent of a film school education when Robson, aware of her directorial ambitions, allowed her to observe its shoot.

“That was very generous of him. He let me look through the camera, he let me review the film’s budget, he let me talk with any of the actors, and I did. It was marvelous. I gained a real understanding of how one sets up a budget for a feature film,” recalled Silver. “I spent about ten days there for my first exposure to the Hollywood moviemaking apparatus …with all the cranes and dollies and budgets and cast and crew. It was very helpful.

“It emboldened me to come back to New York and to make films right away. I said to my husband, ‘I don’t want anybody else to do that to a script of mine.’ And I always remember what he said: ‘Go ahead, jump in the water. If you can’t swim now, you won’t be able to swim ten years from now. This is your chance to try and find out.’ If he had said, ‘Well, what do you know about it? Why don’t you apprentice at film school first?’ I would have probably said, ‘Oh, yeah, you’re right.’ But he didn’t. He gave me support and a sort of permission to try.”

The shorts Silver made helped her hone her skills until she and Ray could pull together the resources to make Hester Street. Besides the novella Yekl, the guts of the movie grew out of Silver’s beguilement with the tales her Russian-Jewish immigrant family told of their coming to America – their crossing, culture shock, and assimilation.

She focused her adaptation on the experience of a young married couple, Jake and Gitl (played by Carol Kane), but in true feminist fashion Silver changed the point of view from the man to the woman. We first meet Jake after he’s already come ahead from the Old Country to America, abandoning allegiance to any cultural traditions he may have brought with him. He sends for Gitl and their son to join him. Informed by Silver’s strong feminist sensibility, Hester Street takes a gritty, witty look at the Jewish immigrant milieu, circa 1896. In her hands it becomes about the awakening of the meek, innocent Gitl who, upon arriving in America, finds her husband an unfaithful scoundrel with no respect for her or their shared past. She’s little more than chattel to Jake. Much to his surprise, she rebels and in the tension between cherished old values and strange new ones, she finds liberation while remaining true to herself and her heritage.

Silver shopped her script around but no studio wanted anything to do with this ethnic period piece, much less her as a director. Since she was not interested in giving control of her script to another filmmaker, Ray set about raising the $350,000 needed to make the film. The couple developed Hester Street themselves under their Midwest Films banner. Ray succeeded in securing the money and Joan shot the film in black-and-white in thirty-four days on a set-dressed section of Morton Street. Interiors were built at a local soundstage. As the budget couldn’t afford a crane for overhead shots, she shot from balconies. One horse stood in for many, dressed differently from scene to scene. Silver modeled her teeming sidewalks on archival images of the Lower East Side taken by Jacob Riis and Lewis Wickes Hine.

Besides no frills, there was no room for wasting time. “The tight production schedule meant added pressure. It was really scary,” said Silver. “I remember one day when I went to shoot a scene and the location had not been secured and it took two hours to secure it, so I was two hours behind, and the whole time I was directing the scene I was thinking, How do I make up the two hours? It isn’t what you should be thinking about when you’re directing a scene.”

She was forever grateful to her collaborators. “I had a chance to work with such good people. I had a wonderful cameraman (Kenneth Van Sickle) and production designing team (Stuart Wurtzel and Edward Haynes) and costumer (Robert Pusilo), and that makes all the difference in the world to somebody just starting out. And I had such a good cast (Steven Keats, Paul Freedman, Doris Roberts, Mel Howard, Dorrie Kavanaugh) and I’m still really close and friendly with Carol (Kane).”

Kane recalled Silver setting a sober, business-like tone on set. “It had to be very serious because it had to happen very fast because we didn’t have a lot of money. We didn’t have any time to waste but she would never sacrifice the essence of a scene for that. Ray was producing. They both had to be very, very, very prepared, which she was, and I think I was too. I think there was a lot of research and work that happened before the camera rolled.

“Our art directors were so brilliant, the costume designer, makeup and hair, our DP (director of photography), everyone was so prepared. And as an actress that was so so helpful to me that I would look around and what I was seeing was what would have been. I was wearing clothes from that time and earrings from that time. Our little set was just a little apartment, and it was so real. It was all there. And everybody was so prepared in working as fast as they could but with a very determined view toward it being right and real. I don’t mean right as in there’s only one right way, but it had to ring true before we moved on.”

It was Kane’s first experience with a woman director.

“I just think a good director is a good director and the sex doesn’t feature in that much,” Kane said. “But I do think at that time some female directors were very tough because they had to be. That’s not my main recollection of Joan. But I know there was a time when there was such a battle to make a movie that some of them were pretty tough.”

Everything came together under Silver’s watch to make a classic. After completing the final edit, she and Ray tried getting a distributor to pick up their evocative period piece. Even after strong reviews at festivals, the couple couldn’t find a buyer. After all the hard work to finance the film, meticulous research to ensure authenticity, and stress to complete the project on a shoestring budget, no one wanted to distribute it. Silver was heartbroken.

“I went through a bad period thinking, I’ve made this film nobody will distribute, what am I going to do? How are we going to pay the money back?”

A desperate Ray cold-called Cassavetes for advice and was told: “Distribute it yourself.” Ray, who has described it as the “most significant call I’ve made in the film business,” released the film with help from Jeff Lipsky. They road-showed the film at individual theaters with whom they directly negotiated terms. Then a funny thing happened. Hester Street caught on. As word of mouth grew, bookings increased, not just in Eastern art cinemas but coast to coast. Ira Deutchman helped get it seen at Jewish community centers, colleges, and universities. To their delight and the industry’s surprise, the little movie found an audience theater by theater, venue by venue, city by city, until it became one of the big indie hits of that era. With a total investment of $400,000, the film grossed more than $5 million.

“I have to give Ray a lot of the credit for that,” Deutchman said. “When people said no to Joan it got him rankled – Oh, how dare they say no – and he’d just figure out a way to get around it. And that happened with the financing of the movie, the actual production of the movie, and the distribution of the film. Ray just kept things moving forward.”

Kane recalled how indefatigable the Silvers were.

“They had this sort of unity of belief in the fact that if something was good and worthwhile it would happen. And, of course, it was a time in film history when that was coming true, when a lot of strange little movies somehow were happening from beautiful scripts about people rather than, you know, giant events. So it was the right time for this little story I guess.”

Kane and Joan felt a connection as each came from a Jewish immigrant family. Kane grew up in Cleveland, where Silver once lived. Kane’s father even knew Ray.

Silver recalled Kane as “a very conscientious, serious, careful, lovely young woman” who went home to rehearse in the sheitel and period jewelry provided for the part.

“I always loved the story, it’s just a great, great story,” Kane said. “When I read the script I saw the movie in my mind. She (Joan Micklin Silver) wrote the movie so beautifully that you could see it, and so I’m just so glad that it materialized in the way it read.”

In 2011 Hester Street was selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.” The citation notes the film’s been “praised for its accuracy of detail and sensitivity to the challenges immigrants faced during their acculturation process.”

The honor took Silver by surprise. “I was really pleased, I had no expectation, and I was delighted to be on the same list with a John Ford movie (The Iron Horse) and a Charlie Chaplin movie (The Kid). It’s pretty exciting,” she said.

On getting news of its induction, Hester Street star Carol Kane said, “It’s a wonderful feeling to feel like something we did was authentic enough and true enough to be valued as something which should be preserved. You know that’s an extraordinary thing because so many movies are made every year and a lot of them just disappear.”

Post-Hester Street, Silver made Bernice Bobs Her Hair for PBS, the features Between the Lines, Chilly Scenes of Winter, Loverboy, Big Girls Don’t Cry, Charms for the Easy Life, Crossing Delancey and A Fish in the Bathtub, and cable movies Finnegan Begin Again, A Private Matter, In the Presence of Mine Enemies, and Hunger Point.

She also produced her husband’s feature directorial debut, the acclaimed 1978 prison film On the Yard, whose co-star, John Heard, played in two of her films.

Her struggles for creative control never went away. There were disputes with studios, planned projects that blew up, deals that went sour. That is just the nature of the business. As Silver once said, “Filmmaking is a tough field for anyone – it’s extraordinarily competitive.” At the time it was that much harder for women. It galled her when men with fewer credits and in some cases no credits at all got opportunities to direct before she did, but she chalked it up as more of the same old shenanigans.

“When I started, there were no women directing at all in the so-called industry,” Silver said. “I actually had an executive say to me, ‘Feature films are expensive to make and expensive to market, and women directors are one more problem we don’t need.’ So, yes, it was that blatant.”

Besides navigating a system in which her gender worked against her, her own idiosyncratic vision may have limited her options. She was attracted to exploring the complex give-and-take of male-female relationships, thus the romantic partners in her films are far from happy and often flounder in search of equilibrium if not bliss. Her barbed, warts-and-all takes on love, leavened by irony and whimsy, are remindful of the work of Ernst Lubitsch, Billy Wilder, Woody Allen, and Alexander Payne. Good company. Except for Hester Street, none of her features were big moneymakers but due to their low costs they didn’t have to be. Her made-for-cable movies scored enough ratings to make her an in-demand talent. She not only broke through the closed system, she largely made movies on her own terms, becoming part of the vanguard of maverick indie filmmakers with John Cassavetes, Robert Downey Sr., and Jon Jost. Between chauvinism in front offices and most critics being men, maverick male directors received more exposure and mythologizing than Silver and her female peers. With time that imbalance has been somewhat corrected.

Pioneer, Advocate, Mentor

More than anything Silver helped lead the way in reasserting women as viable directors for the big and small screen. Not long after she first made her mark, a new crop of American women directors emerged on the scene, including Lee Grant, Susan Seidelman, Amy Heckerling, Martha Coolidge, Claudia Weill, Randa Haines, Donna Deitch, and Barbra Streisand.

Some of these artists were able to sustain careers and some were not. The most commercially successful of them made it easier for new generations of women filmmakers to establish themselves.

Dina Silver, one of Joan’s three daughters, takes pride in that legacy. “Our mother was a cinematic pioneer who became one of the first in a very small cohort of women who were feature film directors.”

The surge of women directors revived interest in Silver’s work. By the end of the 1990s she was regarded a guiding spirit for the vibrant new women’s cinema scene. She served on the advisory board of the New York Women’s Film Festival and was booked as a panelist and expert.

“I used to make it my business to go to every film directed by a woman, just as a kind of show of solidarity” she said, “but I could not possibly do that now because they’re all over the place. They’re making everything from music videos to television films to feature films.”

Often sought out for advice by new filmmakers – male and female alike – she was glad to share her wisdom. “Of course, I’m flattered by it. I enjoy meeting with filmmakers and talking to them and comparing notes. They’re looking for almost any kind of help they can get that might help them get projects off the ground.”

More than most, she appreciated the progress women began making in film again after being left behind so long.

“Absolutely. It’s great,” she said. She attributed this breakthrough as much to women pounding at the gates of opportunity long and hard enough to finally gain entry as to any contribution she and peers made. Whether due to inroads made by these modern pioneers or not, once closed doors have undeniably opened. Her daughters, who grew up on their mother’s movie sets, pursued screen careers of their own. Marisa has directed feature films, although these days she’s raising a family. Dina is a producer. And Claudia is a writer-director.

Of her daughters following her footsteps, Silver said: “I think they all felt at home with the process and I don’t think they had an unrealistically rosy view of it all. They’ve certainly been aware of the various things I’ve gone through, but they’ve seen for the most part that I’ve enjoyed it and am proud of what I’ve achieved and am still at and so on. So, I hope they’ve been encouraged by it.”

Silver was excited by the prospect of a more dynamic cinema emerging from the new talent pool of women and minority filmmakers. “Yeah, it’s going to be a much richer stew, and something all of us can enjoy. Women are definitely in a better place today. Talented women do get opportunities. It’s not nearly as bleak as it once was,” she said in 2011, the year Kathryn Bigelow became the first woman to win a Best Director Oscar (for The Hurt Locker).

Though grateful for the progress, the realist in her knew there was more work to be done. Indeed, while women directors are widely embraced and employed compared to the drought of the 1930s through the ’70s, they still comprise but a fraction of directors in film and television.

While yet to fully assume their rightful place in terms of representation, their contributions to film, past and present, are increasingly noted. In 2017 the UCLA Film and Television Archive inaugurated a new series, What A Difference: Women and Film in the 1970s and 1980s. Silver’s Hester Street was screened in the series.

The 2019 book Hollywood: Her Story, An Illustrated History of Women and the Movies charts how women were systematically pushed out of the way only to fight their way back in. It notes that Silver was among those demanding inclusion. A 2019 New Yorker article, “The Women Who Helped Build Hollywood,” did its part to give early women film pioneers their due. The 2019 book Liberating Hollywood: Women Directors & the Feminist Reform of 1970s American Cinema highlighted the role that filmmakers such as Silver played in bringing women’s voices and sensibilities to directing. A 2021 Vanity Fair article, “Promising Women,” cited Silver as one of the influencers who inspired others to follow her lead.

The website Making It: Women in Film is a compendium of women in film throughout history, one of many resources and research efforts now devoted to women in film.

Sharyn Rothstein, the screenwriter and playwright who adapted Silver’s seminal film into a play, said she feels a debt to Silver and her contemporaries in the 1970s and ’80s for the foundation they laid to give women creatives behind the scenes more opportunities.

Rothstein is conscious she hasn’t faced the obstacles Silver did. That became clear when she spoke with Silver.

“It never got easy – she really stressed that when I met her. It was always a battle. In so many ways I am incredibly fortunate to be the beneficiary of the work and struggles of Joan and her generation of artists.”

Despite strides that Silver and her peers helped make possible for artists like Rothstein, there’s no question that equity issues still abound in film and theater. As evidence that disproportionality continues despite progress, the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Films at San Diego State University found that in 2022 women accounted for only 22 percent of television and film directors. The numbers were not much better for writers, producers, and executive producers. While 30 percent of editors are women, only 8 percent of cinematographers are women.

Why does the struggle for parity continue? Industry purse strings are still controlled by men who are socially and culturally conditioned to trust the bottom line to men. Misogyny, as evidenced by the Harvey Weinstein and assorted other abuse scandals plaguing Hollywood, is deeply rooted in the industry and a sea change will only happen as more women become powerbrokers and decision-makers.

Another indicator of how the system is skewed to favor male directors can be seen in how the industry, the media, and the public have treated Silver and fellow native Nebraska director Alexander Payne. Though her first feature, Hester Street, ended up in the National Film Registry, in terms of recognition it represented the apogee of her career despite the fact she continued producing work for another three decades. Her small, intimate, character-based relationship movies were made on micro budgets with excellent but lesser-known actors.

It didn’t help, as Deutchman points out, that her work largely couldn’t be seen anywhere for some time.

“I was astounded in my teaching by how few of my students had ever heard of Joan Micklin Silver. Part of it was the films were out of circulation or buried somewhere where nobody was checking them out.”

By contrast, Payne has worked with bigger budgets and A-list stars in fashioning his own intimate, character-based relationship movies. His films (About Schmidt, Sideways, The Descendants, Nebraska, Downsizing, The Holdovers) have premiered at major international festivals, gotten wide theatrical releases and been Oscar-nominated multiple times compared to the limited releases and single Oscar nomination Silver’s films received. Consequently, Payne’s films are far better known than hers, which is why her name and the titles of her films don’t resonate with the general public the way his do.

In their shared hometown of Omaha, Silver’s films have never been featured in a program even approaching a retrospective of her work, whereas Payne has been feted in several special events. Part of this imbalance of appreciation and recognition is explained by the fact that Payne has never really left the city while Silver never lived there again after leaving in 1952, making her home in Cleveland and then New York. Attempts to bring Silver back failed except when the Mary Riepma Ross Media Arts Center honored her decades ago. In this out-of-sight, out-of-mind scenario, she and her work became lost to history in her own birthplace, though not in cinema capitals such as New York and Los Angeles.

In Nebraska, the place her movie aspirations were fired, her work deserves retrospective attention from the Omaha art cinema Film Streams, the annual Omaha Film Festival, and the Jewish Federation of Omaha’s annual Jewish Film Festival. To date, none have recognized her or her work. Even though it seems her hometown has forgotten her, she never forgot or disguised her roots, even naming her production company, Midwest Films. An earlier production company was named Omaha Films. She longed to make a Western in the Sandhills.

Navigating Hollywood

Even after Hester Street’s success she still couldn’t get Hollywood backing for her next project, Between the Lines (1977), which examines an underground newspaper staff’s struggles to balance their revolutionary zeal with dollars-and-cents reality. Silver’s gift for casting promising newcomers continued in Between the Lines, which introduced John Heard, Jeff Goldblum, Lindsay Crouse, and Marilu Henner to most viewers.

A major studio, United Artists, did attach itself to her third feature project, Chilly Scenes of Winter, a 1979 film that steers clear of cliches in charting the ups and downs of a romantic relationship. Silver’s association with UA turned sour when the studio ordered a new ending (to a less ambiguous one) and a changed title (to the frivolous Head Over Heels) against her wishes. Her critically praised film was a box office bust, but she ultimately prevailed when she got the UA Classics division to release her director’s cut in 1982. The film reteamed her with Heard, who played opposite Mary Beth Hurt and Peter Riegert.

A decade removed from the UA debacle, she finally danced with the studios again when her Crossing Delancey (adapted from the Susan Sandler play) was picked-up by Warner Bros. The film brought her together again with Riegert, who appeared with Amy Irving.

Then she was brought in as a hired gun to direct two screwball comedies, Loverboy (a 1989 Tri-Star release) and Big Girls Don’t Cry (a 1991 New Line release), she did not originate. While she enjoyed doing the latter two projects, she preferred generating her own material. “In the end it’s more satisfying to me to be able to make films that I just feel more personally,” she said.

Unafraid to tackle the silly, messy, chaotic side of relationships, she probed issues like obsession, desire, infidelity, possessiveness, loneliness, rejection, and regret. Like the smart repartee associated with Lubitsch, Wilder, Cukor or Hawks, her films delight in verbal sparring matches that deflate gender myths and romantic idylls.

Silver’s men and women are equally strong-willed and neurotic. That is never more evident than in Crossing Delancey, where Sam (Peter Riegert), the pickle man, patiently waits for the upwardly mobile Izzy (Amy Irving) to come down off her high horse and finally see him for the decent-if-not-sexy guy he is. The story is also very much about the uneasy melding of old and new Jewish culture and the conflicting agendas of today’s sexual politics. Izzy is the career-minded modern woman. Sam is the tradition-mired male. Each pines for affection and attachment, but are unsure how to get it. In the end, a matchmaker and bubby bring them together.

About the male-female dynamic in her work, Silver said, “That is something I’m quite interested in. Why? I have no idea, other than a life lived, I guess. In my own life experience I had a really wonderful father who was interested in me and paid attention to me and to my ideas… and God knows I have a wonderful, supportive husband whom I’ve had three great daughters with. I haven’t had the experience of abuse by men, so basically what I’ve done is more observe the differences (in the sexes) than the struggles.”

Her 1985 HBO dramedy Finnegan Begin Again starring Mary Tyler Moore, Robert Preston, Sam Waterston, and Silvia Sydney was another foray into romantic entanglements. Working from a script by Walter Lockwood and Silver’s direction, Moore and Preston play longtime partners Finnegan and Liz in search of affection and love. Even though they are long past spring chickens, their desires are full and ripe, indeed maybe even more so now because they’ve matured like a good wine. Silver delivered a sweet movie that never feels maudlin or sentimental – only real.

She depicted romance as a complicated dance that often trips couples up because the partners can’t seem to settle on who leads and who follows or they can’t get the steps right. Though we never quite master romantic relationships, we keep trying. If we’re lucky, we find someone we move in rhythm with. As the movie reminds us, it’s never too late to start.

A Private Matter is a straight drama and Silver demonstrated she could handle heavy material with the sure touch of her lighter fare. It is a true-life tale about a young American married couple with kids who become the center of the thalidomide scandal and tragedy. Sissy Spacek and Aidan Quinn portray Sherri and Bob Finkbine, who discover that the fetus Sherri is carrying will likely be born severely deformed due to the effects of the then widely prescribed drug thalidomide. When their intent to terminate the pregnancy goes public, it sets off a firestorm of controversy that nearly destroys them. In the midst of the medical deliberations, legal wrangling, and media stalkings, the couple learn how widespread abortions are and how secret they’re kept. Silver contrasts sunny, placid 1960s suburban family life with the dark underside of hypocrisy, greed, fear, and hate that surface when issues of morality get inflamed. In this case and cases like it, what should be a private matter becomes a public controversy and the people involved are persecuted for following their own conscience. Estelle Parsons and William H. Macy also appear.

Legacy

Going from shorts to Hollywood features was a long leap, particularly for a woman with no connections to help navigate the bluster and bias of male gatekeepers. Silver overcame all of that to create a three-decade body of work that stands as a testament to a creative spirit that would not take no for an answer.

There is little doubt world cinema is richer for the insistent drive she displayed in becoming a filmmaker even when told she couldn’t be one or wasn’t invited to the club. Though her name remained unfamiliar to most Nebraskans, fellow filmmakers from the state recognized her brilliance.

“Joan Micklin Silver directed wonderful, very human stories,” said Alexander Payne. “Almost all other distinguished movie people from Nebraska migrated to California, but Joan went to New York and became a keen observer and chronicler of life there.”

“She was an unapologetically Jewish filmmaker making films informed by her own cultural experiences. The irony is that most people probably thought she was from New York. But sometimes it takes an Omahan to fully appreciate and comment on New York life,” said SlamDance founder Dan Mirvish, an Omaha native.

She only stopped producing work when her life and creative partner Ray died in 2013 and then dementia stole her mind.

Long before then her example of breaking cinema’s glass ceiling inspired other women to follow her path. One of those who did was the late Gail Levin, a fellow Omaha native who made a name for herself as a feature-length documentarian.

Hester Street will always remain Silver’s legacy because its unexpected and unqualified critical and commercial success helped women break through in Hollywood. As a result, women gained a stronger foothold behind the camera in American cinema, paving the way for more women to call the shots and have their say.

Prior to her illness Silver was writing a book about the making of Hester Street. A biography was also in the works. The film’s enduring impact has now expanded thanks to the stage version by playwright Sharyn Rothstein, with original music by Broadway’s Joel Waggoner. Should it go to Broadway, Silver’s name, work and legacy may finally gain the currency they deserve in Nebraska.

The Silver family was on hand opening night of the Hester Street play. The show received strong reviews. All mentioned Silver’s film as the play’s source material, thus helping further ensure her greatest cinema treasure is recognized.

Dina Silver is sure her mother would be thrilled by Hester Street’s new life.

“Before her health failed, she had begun to work on Hester Street the play and she would be deeply moved and exhilarated to see that the project came to life even after her death. We are excited that mom’s gorgeous commitment to stories that touch the heart has a new life in the play.”

When she sees women-crafted screen projects she hopes some of their makers acknowledge her mother’s pathfinding contributions.

“She would be absolutely thrilled to see the numbers of women putting their individual stamp of heart and intellect on films all over the world, and to have been one of the women who helped nudge the door open.”

Not one to dwell much on what might have been, Joan Micklin Silver felt that an even playing field might have meant more chances but considered her career a validation of women’s gains. “Well, you know, one always feels one could have done more. But I’ve managed to make films for many years now in a field that was extremely unfriendly to women and to make the films I wanted.”

Sidebar: Spotlight on Women Directors

Following Silver’s lead, the films of Nora Ephron, Sofia Coppola, Kathryn Bigelow, Penny Marshall, Joyce Chopra, Betty Thomas, Cheryl Dunye, Julie Dash and Mira Nair made waves and their success helped usher in such new talents as Julie Taymor, Tamara Jenkins, Ava DuVernay, Gina Prince-Bythewood, Jodie Foster, Patty Jenkins, Nancy Meyers, Catherine Hardwicke, Greta Gerwig, Anna Boden, Kelly Reichardt, Chinonye Chukwu and Omaha-born Reed Morano.

(1/30/25: An earlier version of this article identified Ira Deutchman as a New York University professor; this has been corrected to Columbia University.)