What was it like to live as a hobo? And what did hobos experience in Nebraska?

What was it like to live as a hobo? And what did hobos experience in Nebraska? Consider this:

“Word came over the telegraph on June 2, 1904, that a group of hobos were bound for Kearney. Among them were burglars wanted in Grand Island. Kearney police officers positioned themselves on either side of the train, ready to arrest whomever disembarked. Five men hopped off, spotted the police, and scattered. An officer commandeered a bicycle and sped off after a fleeing hobo. A half-mile later he overtook the hobo, but he was not one of the burglars. Asked why he ran, the hobo said police along the Union Pacific line regularly beat anyone stealing rides and he assumed he was next. The officers let him go.”

So begins “Billy Clubs and Vagrancy Laws: Confronting the ‘Plague of Hoboes’ in Nebraska, 1870s-1930s,” in the Winter 2018 issue of Nebraska History.

The topic was a challenge for author Nathan Tye, a doctoral candidate at the Department of History at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. A hobo’s transient lifestyle didn’t produce a lot of written records. A research grant from the Nebraska State Historical Society Foundation helped Tye compile information scattered among multiple sources. (As shown by the quotation below, some men who rode the rails in their youth later wrote about their experiences, and a few former hobos became famous authors.)

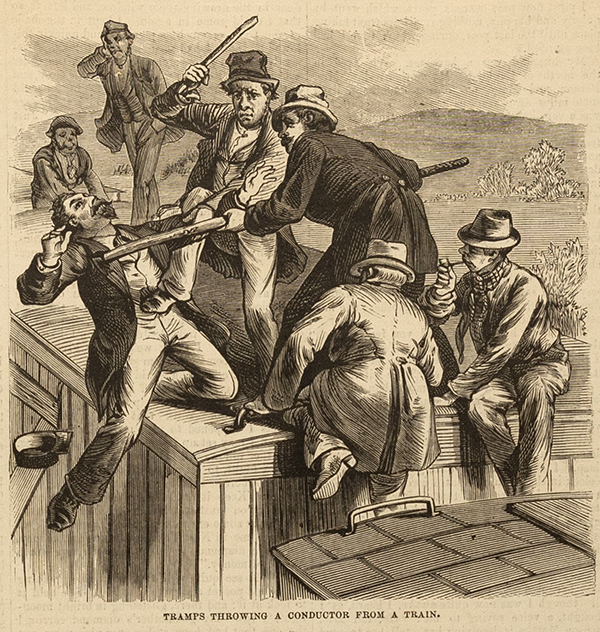

Illustration: From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Feb. 2, 1878. “Tramps,” later known as “hobos” were often portrayed negatively in the press. In reality, it was the hobos themselves who were often violently thrown from trains.

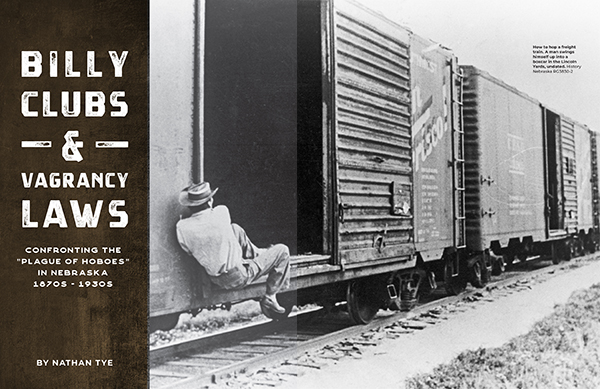

Top of page: Opening spread of Tye’s article in Nebraska History. Undated photo shows a man swinging himself into a boxcar in the Lincoln Yards. History Nebraska RG3830-2

Though later romanticized, hobos were unwelcome wherever they went. Tye writes:

“The most feared perpetrators of anti-hobo violence were not government officials but—as the hobo disclosed to the Kearney police officers in the introduction—the brutal private police officers and detectives hired by railroads to patrol yards and trains. Known to hobos as “bulls,” these men were the bane of hobos everywhere. They threw hobos from moving trains, shook them down for money, and regularly beat them within inches of their lives with billy clubs or brakemen’s clubs. This abuse haunted former hobos for the remainder of their lives. Jack London admitted, “I’ll never get over it. I can’t help it. When a bull reaches, I run.” In 1897, when a nineteen-year-old Carl Sandburg hopped out of a boxcar in McCook’s yard he found “a one-eyed man in a plain clothes with a club and a star stood in my way.” After the bull made it clear his type was not welcome, Sandburg climbed into his boxcar and went east. After a few days filling up on pilfered corn in a hobo jungle outside Aurora, he traveled to Nebraska City where he chopped lumber, picked apples, and slept in a jail cell.”

Sandburg then headed for Omaha, where the Jobbers Canyon warehouse district was known as the “hobo capital” because of its reliance on transient labor.

Photo: “Flophouse on lower Douglas Street, Omaha, Nebraska.” Photo by John Vachon, November 1938. Library of Congress

Farms also relied on transient workers, especially at harvest time. People didn’t like having poor, transient men around—except when they needed cheap labor. Tye argues that “hobos contributed to the development of Nebraska’s agricultural, legal, and social landscapes” but that their “presence is obscured in a historical narrative valorizing sod-busting families and not the hired hands and harvesters who labored alongside them every season.”

* * *

History Nebraska members receive quarterly issues of Nebraska History as part of their membership. Single copies are available from the Nebraska History Museum for $7 (plus sales tax for Nebraska residents and shipping for mail orders).