Objects made by artists that are still living and objects made with modern materials both create interesting challenges and opportunities for conservators.

Objects made by artists that are still living and objects made with modern materials both create interesting challenges and opportunities for conservators.

The sculpture “Sophie-Ntombikayise” by Mary Sibande

The sculpture “Sophie-Ntombikayise” by Mary Sibande is both. According to the University of Kansas Spencer Museum of Art’s website:

Emerging artist Mary Sibande lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa. This work, the first in a U.S. museum collection, culminates Sibande’s series of sculptural installations featuring four generations of women in her family, all of whom worked as domestic servants. The name Sophie comes from a real and imagined collective narrative. The wonderfully overblown gown—an artificial hybrid costume of maid’s uniform and regal Victorian dress—provides the tableau on which Sibande unveils her story. Through Sophie-Ntombikayise, Sibande addresses the “traditional” role of black women in South Africa and other countries with a history of black servitude.

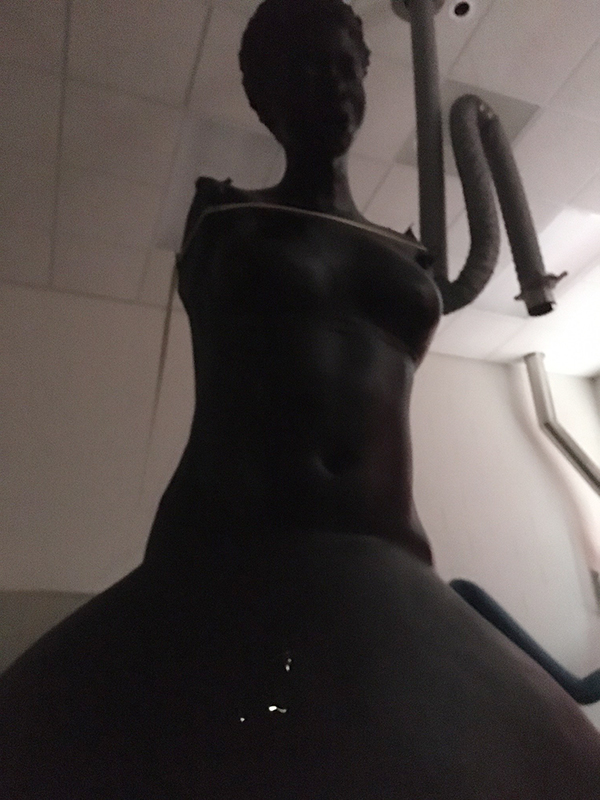

When it was examined for treatment, the sculpture’s arms and the dress it usually wears for exhibit had been removed. The sculpture is composed of a cast resin head and torso of a woman atop a large, hollow dome. One can see layers of clear polyester resin with fiberglass from the inside. Since the resin substrate is clear, the materials applied over it are visible through it. These include layers of yellow and black, which appear to be the filler used to create a smooth surface, and the topcoat of thick, black paint.

The interior form and support of “Sophie- Ntombikayise” with the arms and dress removed for treatment.

The sculpture was in good condition overall. The main concern was the visible cracks formed on the surface of the sculpture’s skirt form. The development of these cracks appeared to be the result of various factors. One factor is the number of materials used to create the skirt form, which are in layers that are not evenly applied. These layers of resin, filler, and thick paint change over time as they age. All respond differently to even the slightest stress or change in environmental conditions, expanding and contracting at different rates. This can result in the separation of the layers.

There is also the issue of stress to the skirt form caused by the torso’s weight on top. The torso is the heaviest element of the piece and is leaning forward from an off-center position at the top of the skirt form, causing stress to the skirt form below.

By shining a light inside the hollow skirt form, the cracks are visible on the outside.

When viewing this area from the underside of the skirt form, points of light could be seen that correspond to the location of the lifting section. When these points of light were examined with a metal probe, the areas appeared to be composed of hard, clear resin. The cracks visible on the top surface of the skirt did not appear to extend through the polyester resin layer.

The museum curator contacted Mary Sibande about the presence of cracks in the skirt. The artist was able to recommend the products and repair techniques she used in her studio. Typically conservators use materials that have been tested for durability, reversibility (or retreatability), and safety to the object and the conservator. However, because the artist is still living and practicing, Objects Conservator, Rebecca Cashman, deferred to her about what materials are best to use to repair Sibande’s work.

To prepare this damaged sculpture to be shipped to the Ford Center, conservator Deborah Long and the Spencer Museum’s preparator worked together to develop ideas for support. The goal was to create a “permanent support” that the sculpture could remain on during transport, storage, and even display, hiding it under the figure’s dramatic skirt. The Spencer Museum’s preparator created a platform with a telescoping seat that could be adjusted internally to rest right under the flat surface at the top of the skirt interior, under the torso. This would add some support to the torso and help the sculpture stay in position during travel.

Ford Center staff unpack the Sibande sculpture from its crate.

When the sculpture arrived at the Ford Center, it was easily removed from its large crate by sliding it out using the handles on its new permanent support.

The first step in treatment was to re-examine the sculpture and investigate again for cracks. It was easiest to do this by elevating the sculpture onto two tables and exploring the inside of the skirt with a light. Cracks not visible to the naked eye were suddenly revealed as the light shone through. Tests with a probe confirmed there were still no complete cracks running through the cast resin substrate, which was great news. All cracked areas visible were circled with pink pastel on both the inside and outside to keep track of them when the illumination source was gone.

Left: Objects Conservator, Rebecca Cashman, examines the sculpture from the inside. Right: Rebecca marks the cracks on the inside of the skirt form.

After photo documentation of the sculpture’s condition, the piece was vacuumed overall, washing the surface with sponges using a gentle anionic detergent and rinsing with deionized water.

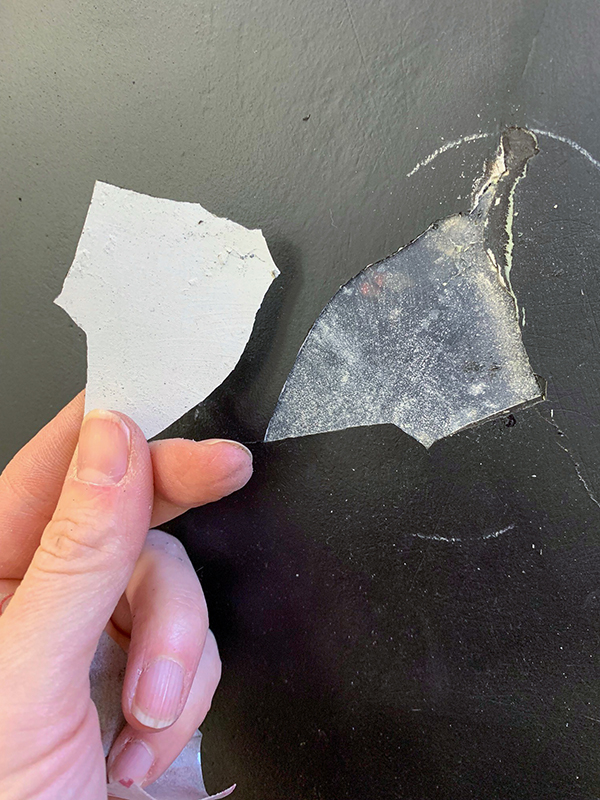

An area of lifting paint and filler was removed.

During the next step, all cracked material areas were removed with scalpels and abrasives. At the top of the skirt, behind the torso, the top layer of the resin exhibited an incomplete hairline crack, likely due to the inevitable flexing of the curved resin skirt over time. Other cracks, such as those on the front of the skirt, extended only through the painted body filler, which had become detached and was lifting from the resin substrate below.

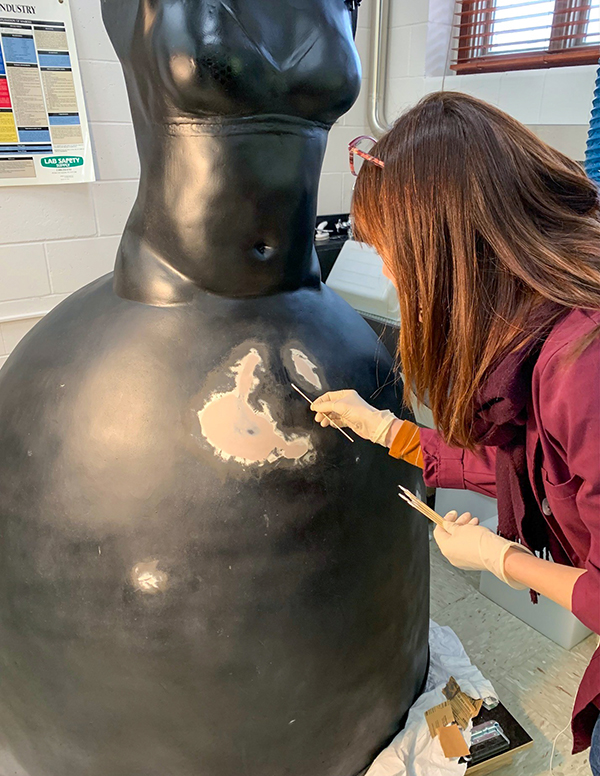

The surfaces to be repaired were abraded and then obsessively cleaned of particulates to prepare them for fills. Fills were made by building up thin layers of the artist’s filler of choice. Once cured, these fills were sanded down to be level with the surrounding surface.

An earlier examination of the sculpture under long and short wave ultraviolet radiation had revealed streaky areas of both orange fluorescence and black absorption, indicating more than one type of paint or coating was on the surface of the skirt. Solubility tests with a range of solvents confirmed this suspicion; the paint at the front center of the skirt was soluble in different solvents than that on the sides of the skirt. The artist had told Spencer Museum Staff that automotive paint should be thinned and sprayed over the repairs. In addition, it might be necessary to spray the entire sculpture with the paint to visually integrate the repairs. As it turned out, it was necessary to spray the whole skirt to achieve uniformity. To choose an automotive paint compatible with the autobody fillers and the two types of automotive paint present, conservators sought recommendations from automotive paint experts at Colorvision of Omaha.

The areas where the paint was lost are filled and sanded before being painted.

Layers of a flexible, buildable acrylic primer were applied to the fills on the skirt. The primed fillers were then rubbed, and the excess particles removed. Once the fillers were properly primed, the torso of the sculpture was covered with plastic to protect it during the painting of the skirt. Finally, the full skirt was repainted with an HVLP sprayer using acrylic enamel paint that matched the color and gloss of the original surface.

The Sibande sculpture, after treatment.

The sculpture was returned to its crate to be shipped back to the Spencer Museum. With new support and the cracks repaired, “Sophie-Ntombikayise” will be better supported for long-term preservation and future display.