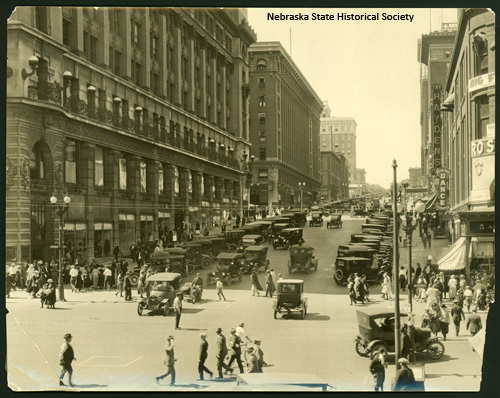

Downtown Omaha, 1920s. Looking west on Douglas Street from the intersection of Sixteenth Street. The Brandeis Building, which still stands, is on the left. NSHS RG2341-58

For many years, Sixteenth Street was downtown Omaha’s main street. Tenth Street and the riverfront have become more prominent in recent years. (The riverfront used to be an industrial zone, as shown in this 1934 photo.) In Janet R Daly Bednarek article “Creating an ‘Image Center’: Reimagining Omaha’s Downtown and Riverfront, 1986-2003,” (Nebraska History 90, No. 4, Winter 2009), she explains what happened and why. In July 2001 the city of Omaha officially dedicated a new city park. The twenty-three-acre riverfront site was formerly home to the Asarco lead refinery, an enterprise with roots in the 1870s and a symbol of Omaha’s early industrial development. Initially, the city council approved the name “Union Labor Plaza.” However, after an election in May 2001, which witnessed the ousting of the incumbent mayor and five city council members, the new mayor and council decided to review the earlier choice. After asking for public input, the council decided on “Lewis and Clark Landing.” In many ways the new name was perhaps more fitting given the decided transformation of Omaha’s downtown and riverfront involving not only the new park, but also a host of other developments from the ConAgra headquarters project in the late 1980s to a burst of large-scale corporate, civic, and residential projects in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Omaha’s leaders had first promoted “back to the river” ideas in the late 1960s and early 1970s. By the early twenty-first century, those ideas witnessed a full flowering. Omaha’s return to the river, though, involved not just massive physical transformation, but an extensive reconceptualization of the downtown and riverfront. Omaha’s historic downtown riverfront had been home to commerce, transportation and industry. Omaha’s new downtown riverfront was home to open space, recreation, leisure and cultural amenities. “Union Labor Plaza” evoked the historic, somewhat gritty downtown riverfront. “Lewis and Clark Landing,” on the other hand, hearkened back to a past that pre-dated Omaha itself by a half century and evoked more pristine images of frontier, wilderness and adventure. Though the plaza eventually held a statue dedicated to Omaha’s working people, the choice of name suggested the degree to which Omaha’s civic leadership had re-conceptualized and transformed the downtown and riverfront to serve as a new “image center” for the city. Though certainly no longer functioning as the center of America’s urban areas, downtowns still command a great deal of the attention, energy, and imagination of those concerned with the future of America’s cities. Downtown history has also proved of interest to urban historians. The last decade in particular has witnessed the publication of two major works on the history of this crucial urban area. Robert M. Fogelson’s work is essentially a political history of the downtown, focused, as he said, on power–who held it, how they exercised it, and how that shaped downtowns from the 1880s to the 1950s. Alison Isenberg, on the other hand, has produced a social and cultural history of the nation’s downtowns, taking the story into the 1960s. To read on click here. Details from the photo provide below show vignettes of city life: Across the nation, the role of downtowns changed dramatically in the twentieth century. The above photo shows one big difference: look at all the pedestrian traffic (not to mention the chaotic traffic control). In the 1920s downtown was still the city’s main retail center.