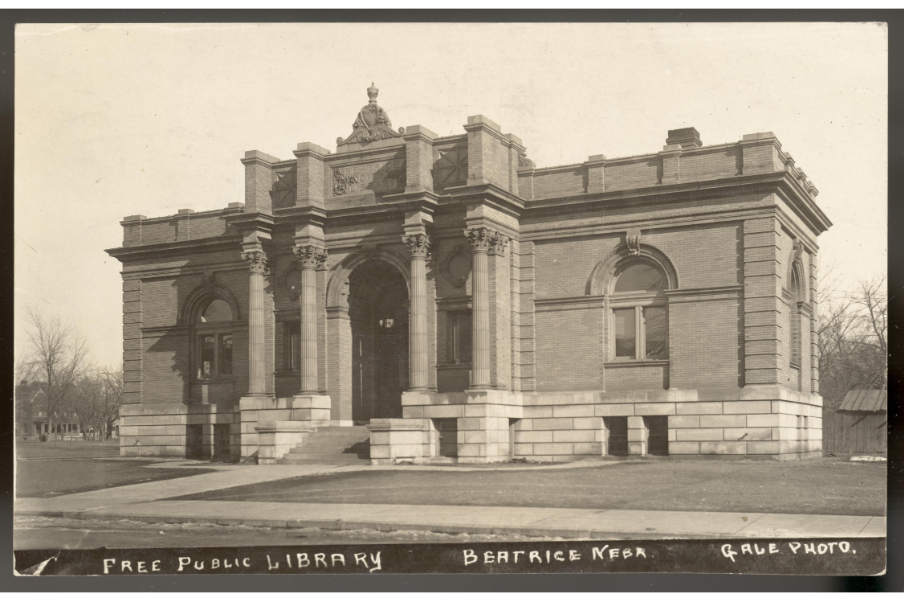

1910 photo of the Beatrice Public Library, Beatrice, Nebraska.

The decade of the 1870s was a period of enormous growth and prosperity for the city of Beatrice. Founded in 1857 in Gage County on the Big Blue River, the “Queen City of the Blue” grew slowly until the arrival of a reliable stage route in 1868, and rail in 1871. Organized as a city in 1872, by 1873 the population had increased to more than 1,000. Occupying the county seat, Beatrice boasted its permanence in fine stone and brick buildings, upscale residences, and vigorous mercantile and industrial districts. Churches had taken root; the common school enrolled 260 pupils and was taught nine months of the year. The county courthouse and the land office for the southern portion of the state were located in town, and commerce and trade boomed. The production of lumber, coal, and flour employed many residents, and the Beatrice Express boasted that citizens could patronize “six general stores, two drug stores, three hardware stores, two furniture stores, one agricultural depot, five blacksmith shops, two harness shops, two shoe shops, two jewelers, four milliners, six carpenter shops, two wagon shops, two tin shops, two butcher shops, one barber shop, one bakery, one brewery, two banks, two livery stables, half a dozen or more boarding houses, three restaurants and two saloons.” These businesses were not, as Nebraska historian A. T. Andreas explained, “built for temporary use by capitalists expecting to soon reap an abundant fortune and return in a few years to the East to enjoy it, but on the contrary, by men who have located here permanently, for the purpose of making this their home.” But permanent prosperity for Beatrice also meant it would need to design itself as a place where the best women and men of this new America in the West would want to stay. Business, industry, and agriculture put food on the table, but left the improved mind hungry for more. Not surprisingly then, the wives of men intent on building business determined that Beatrice would have amenities to build the town’s society and culture-and within a short period, there sprang up a variety of clubs and organizations designed to edify residents. Among those groups was one focused on establishing a public library.

As historians of libraries in the West have shown, public libraries were an important benchmark of respectability, especially in the emerging West in the years preceding the establishment of professional public librarianships and government-run public libraries. The social institution of the library reflected a community’s progressive cultural values in that it provided democratic opportunities for recreation, self-improvement, and Americanization. Libraries were also seen as a civilizing influence and as a vehicle for civic reform-especially during the early years of the temperance era when many positioned libraries as an institution that could support moral order and serve as an antidote to the scourge of liquor and other less wholesome pursuits. Women’s associations served an important role in culture-building and reform throughout the West during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era; however, in comparison to historical work on other cultural institutions, there have been few studies of what historian Paula D. Watson notes as women’s “massive, nationwide influence on the growth of one of our most important public institutions, especially outside of the urban areas of the northeast.” Similarly, historian Anne Firor Scott has called for an examination of women’s roles in the early years of the public library movement in order to better understand “the tremendous social change represented by the education of women, the development of women’s organizations, and then the movement of women into public political activity.” In other words, educated, civic-minded women used public libraries for building community and fostering municipal pride through cultural enrichment. Libraries were also a means for propagating social values and creating pathways for women to enter into civic dialogue and larger social roles. The public library of Beatrice fits this model; as a result, the history of the earliest years of public library activity in Beatrice is best told by beginning with the association of women who were instrumental to its founding and development. Especially important is one woman at the center of that activity: Clara Bewick Colby, Beatrice’s first librarian, whose vision and volunteerism sustained library activity during the 1870s.

The entire essay written by Kristin Mapel Bloomberg appears in the Winter 2011 issue.