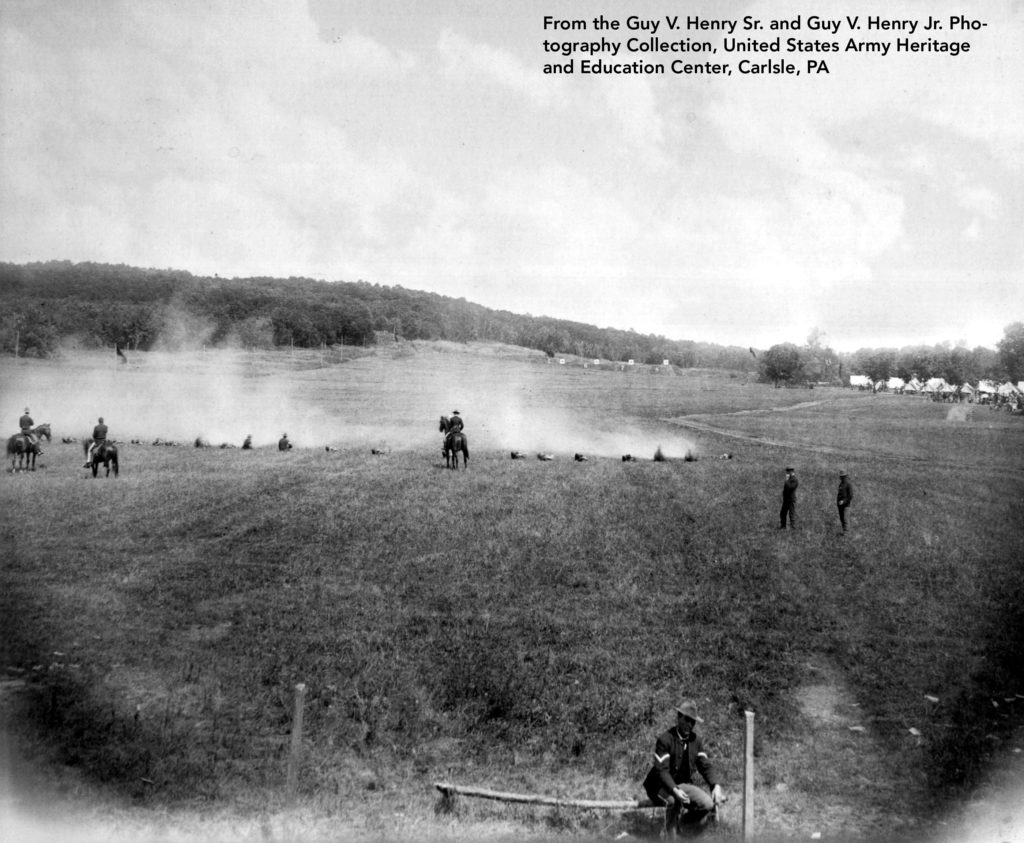

In this 1888 image of the Bellevue rifle range, the men are firing from prone or sitting positions. The targets appear in the distance, with the enlisted men’s camp visible at right. The black powder cartridges used in the army’s Springfield rifles and carbines produced clouds of white smoke. The view is to the north/northwest.

In this 1888 image of the Bellevue rifle range, the men are firing from prone or sitting positions. The targets appear in the distance, with the enlisted men’s camp visible at right. The black powder cartridges used in the army’s Springfield rifles and carbines produced clouds of white smoke. The view is to the north/northwest.

Between 1882 and 1894 U.S. soldiers fired lead bullets by the ton into the butts of the Department of the Platte’s target ranges first located near Fort Omaha and later near Bellevue, some ten miles southeast of the fort. Some of these missiles probably remain buried beneath the modern landscape. Physical evidence of the ranges themselves, like the clouds of black powder smoke that issued from the rifles of the soldiers who used them, has long since disappeared. Yet their story can be resurrected from the historical record to reveal how a system of target practice initiated in the last quarter of the nineteenth century helped produce an “army of marksmen” by the early years of the twentieth.[1] The story of these target ranges and the soldiers who built and used them is told in the Summer 2016 issue of Nebraska History in the article “‘Uncle Sam’s Sharpshooters’: Military Marksmanship at Fort Omaha and Bellevue, 1882-1894” by the late NSHS historian and associate editor Jim Potter. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, training soldiers to shoot with accuracy was low on the U.S. Army’s list of priorities even as it adopted new weapons capable of doing so. Civil War volunteers received little if any instruction beyond how to load and fire their guns as rapidly as possible. According to the tactics of the day, mass volleys from soldiers deployed in ranks were expected to decimate an enemy force by the sheer number of bullets sent in its direction; taking time to aim at individual combatants would actually slow the rate of fire. Later, during the Plains Indian wars, U. S. soldiers’ deficiency in marksmanship became painfully evident during encounters with an elusive foe who fought individually or in small groups and often emerged unscathed by army bullets. Not until the early 1880s, after the Indian wars were nearly over, did the army brass take significant steps to address these shortcomings. They realized that future wars would be waged against foreign armies that were far more disciplined and better armed than the Plains tribes. In the post-bellum years, Nebraska was within the army’s Department of the Platte, whose headquarters were in Omaha. In 1873 department commander Brig. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord took some of the earliest steps to train soldiers to become better shots. He ordered post and company officers to oversee weekly target practice at the department’s various stations, and published the results in the Army and Navy Journal, including the highest and lowest scores and the names of the respective company commanders. Another of his orders authorized post commanders to use lumber on hand to build target frames because “Recent campaigns against Indians have demonstrated that it is better to expend lumber for targets than for coffins.” After being reassigned to command the Department of Texas, Ord continued to promote target practice and issued a grim but practical admonition: “The soldier is armed so that he may, in battle, hurt somebody with his rifle, and the sooner he learns to do so the better the soldier.”[2]

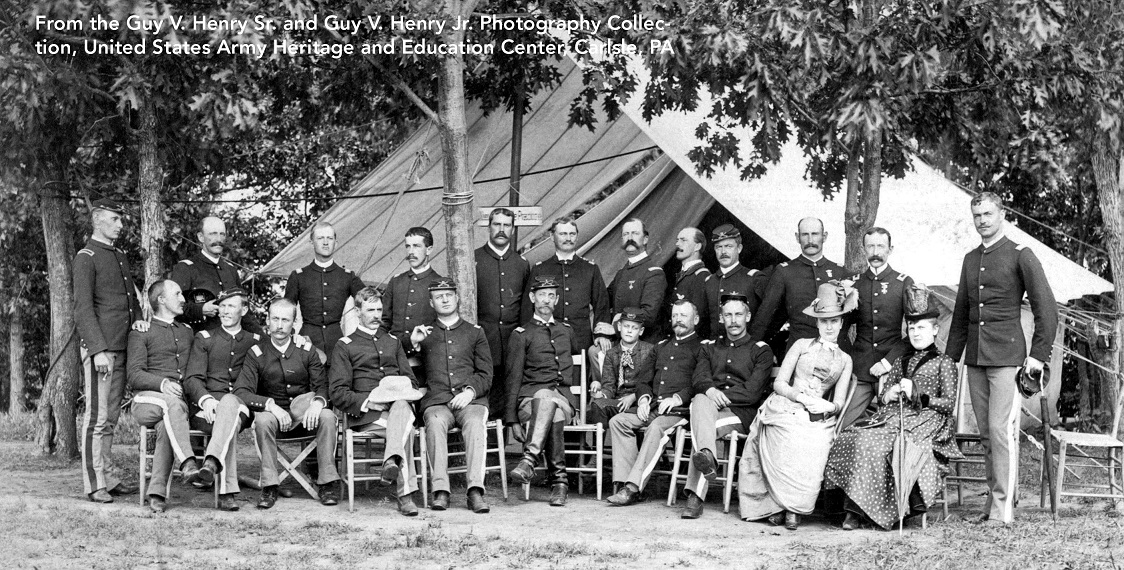

This 1890s image confirms the Bellevue range’s attraction for civilians due both to its park-like setting and the marksmanship contests held there. The officer seated center with the girl on his lap is Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke, who commanded the Dept. of the Platte from 1888 to 1895. NSHS RG2499.PH.1-15

This 1890s image confirms the Bellevue range’s attraction for civilians due both to its park-like setting and the marksmanship contests held there. The officer seated center with the girl on his lap is Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke, who commanded the Dept. of the Platte from 1888 to 1895. NSHS RG2499.PH.1-15

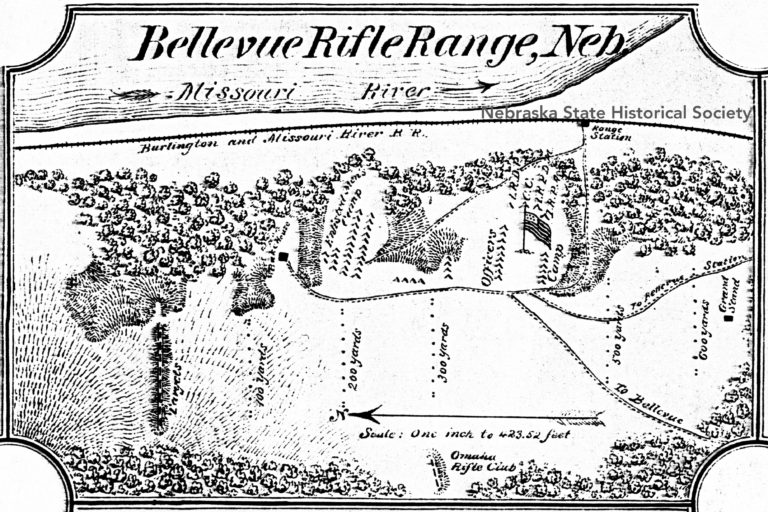

During the remainder of the 1870s, the army took halting steps toward developing a systematic marksmanship training program, spurred on by Indian wars demonstrating that many soldiers still remained ill-prepared to “hurt somebody” in battle. In 1876 the number of cartridges allocated to each soldier for monthly target practice was increased from ten to twenty. A new manual for rifle instruction was adopted in 1879, and the army ordnance department was delegated to provide ammunition and standardized targets, the latter based on those used by the National Rifle Association. The quartermaster’s department was made responsible for the funding to build and maintain rifle ranges.[3] Fort Omaha faced particular challenges in providing marksmanship training for the soldiers stationed there. Established as Omaha Barracks in 1868 and located three miles north of Omaha, the fort’s military reservation encompassed only 85.5 acres. By 1878 when the barracks was declared a permanent post and renamed Fort Omaha, the area to the south and west remained primarily agricultural, although several subdivisions had been platted to the east and southeast. The fort’s proximity to civilian land holdings and its constricted military reservation made establishing a suitable target range problematic.[4] Compared to former Fort Omaha ranges, the one the Army later built near Bellevue was nearly ideal. Not only was it easily accessible via the B & M Railroad, enough land could be cleared for campsites and the firing range itself while still leaving a surrounding belt of woodlands for shade and to break the wind.

Detail from “Military Posts and Reservations in the Department of the Platte,” ca. 1890. Brig. Gen. William Carey Brown Collection, National Archives and Records Administration

Detail from “Military Posts and Reservations in the Department of the Platte,” ca. 1890. Brig. Gen. William Carey Brown Collection, National Archives and Records Administration

The area encompassing the target pit and firing stations was some 800 yards long and 500 yards wide, easily accommodating eight shooters at fixed firing points and providing the required 600 yards for both “known distance” and skirmish firing. The targets stood at the north end, insuring that the sun would not be in the marksmen’s eyes at any time of the day. A grandstand for officials and spectators, connected to the target pit by telephone, was at the south end. In its technical aspects, the range conformed well to army requirements. As the campsites signaled, its distance from Fort Omaha meant that soldiers who used it during practice sessions and official competitions would bivouac on site. Water was provided by a well; a bake house was built near the enlisted men’s camp. In the summer of 1887 the railroad added a “range depot” or platform about 200 yards from the range itself where competitors and spectators could disembark. Supply wagons could reach the range via a mail road from Omaha that skirted it on the west and south.[5] Just before the first Department of the Platte competition was set to begin on the new range, a severe storm threatened the hard work Major Henry and his men had put in getting it ready. Shortly after midnight on August 13, 1886 (Friday, the thirteenth), “a tornado of wind, floods of water, and most vivid lightning” blew down forty-seven tents, swept rifles, carbines, and even a mule into the tops of trees, and injured several men. The anonymous soldier-journalist who reported the storm to the Army and Navy Journal joked that he and his comrades were now fully qualified to advise other marksmen about “points on the wind” at the Bellevue range.[6]

Maj. Guy V. Henry and his son, Guy V. Henry Jr., are seated at center in this 1888 photograph of what is likely the cadre of officers in charge of the matches.

Although the nineteenth-century army was segregated, soldiers from the African American cavalry and infantry regiments were eligible for the marksmanship competitions, including those held at Bellevue. Corp. Beaman Walker, Co. A, Ninth U.S. Cavalry, stationed at Fort Niobrara, earned a place on the Department of the Platte rifle team in 1887. Other representatives of the black regiments included Sgt. James F. Jackson from Co. G, Ninth Cavalry at Fort Robinson, who garnered recognition as a “distinguished marksman” in 1889, 1890, 1892, 1893, and 1894. William Mason, a private in Co. B of the Ninth at Fort DuChesne, Utah, when he first shot at Bellevue, later transferred to the Tenth Cavalry, where he continued to rank high in carbine and revolver competitions. Spencer Thomas, a private in Co. A, Ninth Cavalry at Fort Robinson, became the eighth-ranked marksman at the Bellevue competition in 1890. After promotion to corporal and transfer to Co. H of the Ninth, Thomas ranked number two on the army carbine team in 1894. As late as 1905, he was still making scores qualifying him as a distinguished marksman.[7] In 1891 the secretary of war authorized one troop in each of several regular army cavalry regiments to be composed entirely of Indians commanded by white officers. Unlike the Indian auxiliaries the army had previously employed for short-term service, these men were enlisted for five years, issued standard uniforms and arms, and trained as other soldiers. Troop L of the Sixth Cavalry at Fort Niobrara enlisted Brulé men from the nearby Rosebud Reservation. Although regulations barred the Indian soldiers from participating in the army marksmanship matches, Sgt. Fast Dog of Troop L, who had apparently demonstrated skill on the Fort Niobrara range, was mistakenly ordered to Bellevue for the 1893 cavalry competition. Once he was there, Department of the Platte commander Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke allowed him “to take the prescribed course of firing along with competitors regularly detailed.” Fast Dog placed twenty-first out of thirty-seven shooters with the carbine and second with the revolver. When these “astonishing” scores became known, the officers at the range clubbed together to purchase a non-military medal for Fast Dog. In presenting it, General Brooke remarked, “I want you to wear this medal as a symbol of what the Indian can do under proper surroundings. Let it be a talisman of priceless value because you have won it against white and colored alike. I deeply regret that you could not have been permitted to wear a medal made by the nation.” No such episode would happen again, however, because the army ended its experiment with enlisted Indian soldiers in 1894.[8]

Looking southeast from behind the target pits at the Bellevue range. The men hold markers that were raised in front of the target each time it was struck by a marksman’s bullet.

Looking southeast from behind the target pits at the Bellevue range. The men hold markers that were raised in front of the target each time it was struck by a marksman’s bullet.

Not only did the army’s marksmanship activities at the Bellevue range spark considerable press coverage, including reports of the scores being made, they also drew crowds of civilians. The availability of rail transportation to the range’s very doorstep was no doubt a factor, as was its park-like setting where citizens could enjoy an “outing.” The opportunity to associate with uniformed young men who displayed admirable skill at their profession of arms gave the visits an added aura of romanticism. In fact, Major Henry had encouraged civilian interest in the Bellevue range by helping to organize an Omaha rifle club, which was allowed to use a small range constructed adjacent to the army range. The citizens’ club was “composed of some of the leading men of Omaha; eminent lawyers, doctors, real estate men, railroad men, and merchants.” Every Wednesday during the summer of 1887 a special car delivered the club members, and “the fair ones of Omaha” accompanying them, to the range. Those who did not wish to shoot could rest in the shade, visit the army rifle camp, or stroll in the woods.[9] The first Department of the Platte competition held at the Bellevue range concluded on August 28, 1886. To read details about this competition as well as the rest of the Bellevue range’s history, purchase the Summer 2016 issue of Nebraska History! You can also order a subscription by calling 1-800-833-6747 or 402-471-3272 or by visiting our subscription site. Sections of this blog are excerpted directly from Potter’s article. Bibliography /Further Reading [1] The best review of marksmanship training during this period is Douglas C. McChristian, An Army of Marksmen: The Development of United States Army Marksmanship in the 19th Century (Fort Collins, CO: The Old Army Press, 1981). [2] Army and Navy Journal, Jan. 11, 1873:341, June 21, 1873:712, May 15, 1875:628 (hereafter ANJ). [3] McChristian, Army of Marksmen, 34-48, passim. [4] Fred M. Greguras, “Omaha, Nebraska: Command and Support Center, The History of the Post of Omaha, Fort Omaha, Fort Crook, and the Quartermaster Depots,” unpublished manuscript, May 17, 1999, 3, 5. [5] The range was described in some detail by the ANJ, Aug. 21, 1886:68, and Omaha Daily Bee, Aug. 22, 1886:9. [6] ANJ, Aug.21, 1886:72. [7] ANJ, Aug. 27, 1887:83; Frank N. Schubert, comp., On the Trail of the Buffalo Soldier: Biographies of African Americans in the U.S. Army, 1866-1917 (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1995), 221, 337; Irene Schubert and Frank N. Schubert, comps., On the Trail of the Buffalo Soldier II: New and Revised Biographies of African Americans in the U.S. Army, 1866-1917 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2004), 198, 288-89. [8] Don Rickey, Jr., “Warrior-Soldiers: The All-Indian ‘L’ Troop, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in the Early 1890s,” in Ray Brandes, ed., Troopers West: Military and Indian Affairs on the American Frontier (San Diego, CA: Frontier Heritage Press, 1970), 41-61; ANJ, Sept. 2, 1893:27; Omaha Daily Bee, Aug. 20, 1893:7. [9] ANJ, June 25, 1887:952.