Lakeland sod high school is under construction. Summer 1934 RG4290.PH0-001505

Lakeland sod high school is under construction. Summer 1934 RG4290.PH0-001505

Our Sod Schoolhouse Marker Monday and Throwback Thursday posts were so popular that we’ve also dedicated Flashback Friday to pioneer schools. The following accounts, many of them first-hand from the pioneers themselves, is information that was excerpted from Book Three of Nebraska Folklore. This book was written and compiled by the Workers of the Writers’ Program in the Work Projects Administration in 1941. You can find Book 3 in its entirety by clicking here. Early School Buildings The school houses that were built before public tax agencies had been established were usually built by the settlers themselves. Three settlers in Saline County dug a school house out of a cave along the bank of the Blue River in 1866. Lumber for the floor and roof was obtained from railroad land fourteen miles away. From there it was hauled to a local mill and sawed into boards. A fireplace, likewise dug out of the river bank, was used for heating. The wife of one of the settlers taught the first school term. Thirteen children attended. Sometimes the simplest necessities for building were entirely lacking: Charles Lederer had no nails when he built a school in Blair County in 1877. In this instance, with true pioneer ingenuity, the sills and studding were joined together by mortises and wooden pegs. Nebraska School Buildings and Grounds, a bulletin published by the State Superintendent in 1902, describes a school erected in Scotts Bluff County in 1886 or ’87 that had walls of baled straw, a sod roof, and a dirt floor. This strange building was 16 feet long, 12 feet wide and 7 feet high. Two years after its erection, cattle, on range in the vicinity, literally ate it to pieces.

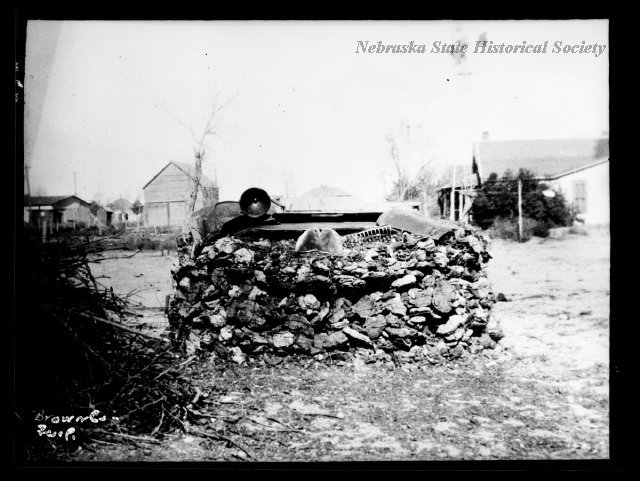

This view shows a stack of cow chips gathered by FERA labor. It is to be used as fuel for the Lakeland sod high school. A scoop, rake and other gathering equipment hold down the pile and protect the chips from the weather. RG4290.PH0-002951

This view shows a stack of cow chips gathered by FERA labor. It is to be used as fuel for the Lakeland sod high school. A scoop, rake and other gathering equipment hold down the pile and protect the chips from the weather. RG4290.PH0-002951

Arta Ethlyn Kochen of North Platte taught in a sod school in 1901. She wrote: “The schoolhouse was a long, low sod building with hills on either side. There were two rooms, school-room and another where the children played. I called it the gymnasium. The rough dirt walls had been smeared over with some sort of a sand mixture and then whitewashed. One or both coats had broken off in places, leaving blotches of brown, white or the bare black earth. There were two little crooked windows. One of these we curtained with daisy chains made of bright papers. This, to me, seemed pitiful, but to the children it was a most wonderful creation. In the other we stowed the pail of water. This had been carried a mile over the hill in the open pail and was peppered with sand. Nevertheless, it served to wash down that big lump that came to my throat so often the first week. The door was of rough pine and opened just far enough to allow one person to squeeze in. We propped it open with a sunflower stalk. There was a floor in the schoolroom, but about the third week one of the men of the district helped himself to that of the ‘gym.’ The schoolroom furniture consisted of a rickety table, a broken rocking chair, two good chairs donated temporarily, two others with broken backs, a cracker box and a soap box. The blackboard was a piece of a man’s rubber coat tacked on the rough wall. The roof was of branches covered with sod, but almost anywhere I could look up and see the little white clouds floating by. . . . The second day a snake a yard and a half long entered the schoolroom and was dispatched with an umbrella. One day I entered the schoolroom to find two inches of water on the floor and rain coming from the sod roof almost as hard as it had come from the sky in the night. Our pictures and paper curtain were a sorry sight. The few books were saturated, and I would have cried had it not been for the reassuring croak of a frog. In such surroundings I taught for two months. Our county superintendent then used her influence to have grain removed from another little house in the district, and the last four months of the term were spent in quarters somewhat more comfortable. A few old desks were given us by the city schools, for which we were very thankful. In spite of such difficulties the interest of ‘My Six’ never waned. They were all eager to learn; they were used to hardships of all sorts; they did not mind the heat of the sun and never complained when the sand burned or the prickly cactus made their little feet bleed; they would come on the coldest days though they froze their hands and ears. And thus amidst such difficulties and hardships the boys and girls who are to be the very warp and woof of the Great West are being trained for citizenship.”[1] Ellsworth Paine, who combined farming with teaching school in Gosper County during the early ’80’s, gives the following description of the school where he taught: The school house was picturesque both inside and out. On approaching it from the southeast it appeared to have bulged up and out of the ground to a height of four or five feet. A rusty stovepipe protruded through the top of a dirt roof. The roof was supported by timbers. From the adjacent background two partially transparent windows broke the monotony of the low sod wall. The door facing the south was approached by a short trench from the creek bank. This door of undressed boards was especially designed for timid “school mams” who desired to inspect their room before entering. By applying the eye to one of the copious cracks, one was able to command a good view of the interior.” Many of the early schools were held in strange places–such as tents, a room or corner of a settler’s home, a granary, a dugout, or church, until the community became prosperous enough to erect a school building. J.B. Jones, who taught in Custer County in 1887, says his school had been excavated out of the side of a hill. On the top and back of the school house corn for fuel was stored. Wandering pigs often raided the fuel supply by running across the roof of the school. According to S. G. Jacoby, who attended school in Sioux County in the 70’s, gophers were another nuisance. Mr. Jacoby says they sometimes tunneled their way into the school room through the earth floor. Mrs. M. A. Springer, who attended school in Dakota County in the ’70’s, recalls an afternoon when the entire school had to vacate the building through a window because a large rattlesnake stood guard at the door. Mrs. Lola Bradbury McComb of Wilsonville, Nebraska, remembers the buffalo that, like Mary’s fabled lamb, followed the children to school each morning. She says, “He was a tame friendly fellow that spent hours nibbling at the grass in front of our door, but he always seemed to be resting in the doorway when we wanted to go in or out of the door. And he wouldn’t move. Many a bare leg scrambled over the shaggy side of our schoolhouse buffalo as we went in and out of the door.” Grant Essex, of Lincoln, who has lived in the State since 1878, says the school house of pioneer days was never locked because it was often used as a haven during a storm or other emergency. A few sandhill schools were also stocked with food caches for travelers who became lost or caught in severe storms. This custom was dropped when it was found that travelers used the supplies in fair weather or when there was no real emergency.

The Lakeland sod high school after it was completed in 1934. A note on a print indicates it was built as a NERA work project. RG4290.PH0-001545

The Lakeland sod high school after it was completed in 1934. A note on a print indicates it was built as a NERA work project. RG4290.PH0-001545

Equipment The equipment and furnishings of the early schools were often as primitive as were the school houses themselves. The County Superintendent’s school report for District 16 in Seward County from 1874 was typical of many schools: H. Williams, director; Miss Caroline Jenson, teacher. Deportment behavior of students, fairly good; recitations pretty well conducted. An old sod house, poorly lighted and ventilated; no cupboard for books, maps, etc.; no hooks for hats, caps, etc.; no out houses; furnished with board seats and desks. School house and seats wholly inadequate for the number of pupils. No recitation seats; no chair for teacher; teacher’s desk; 24 feet of blackboard surface; no globes, maps, charts, dictionary or books of reference. Pupils in the district, 47; enrolled, 34; present 25; average attendance, 29. No visits by director. Several visits by parents. In Crete, in 1878, the teacher’s chair was a nail keg, the desk was made out of an organ. J. Estella Allen says that in her school, in Fillmore County during the ’70’s, they used for desks, rough tables, none of which had been scaled down to fit the different ages and sizes of the children. When there weren’t enough benches to go around, as was often the case, the children sat on the floor. Too often this was a dirt floor, dusty in dry weather or muddy with pools of water from a leaky roof, following a rain. Isabell Cornish, who taught in Custer County in the early ’80’s, says that her first blackboard was made by applying a coating of soot and oil to six feet of builder’s paper. When the commercially-made slate came into vogue it made school work easy for both teacher and pupils. The boys usually erased their figuring or writing by spitting on the slate and then rubbing it off with their coat sleeves. The girls, more fastidious, carried pieces of cloth with which they washed their slates after wetting the rag at the water pail. The chalk for these blackboards, according to L. W. Conklin, who taught in Saunders County in the ’70’s, was sometimes made of soft white rock found in the gullies. Soapstone was also used. Purple ink, according to Grant Essex, who attended school in Chase County during the early ’70’s, was made by steeping poke-weed berries in water. Nicholas Sharp, who taught near Liberty, Nebraska, in 1870, says he also made his own ink. Either powder or indelible sticks were used, with water added. Stove soot, with oil, was also used. This strange concoction, being thick, resembled printer’s ink. The quill pens were, likewise, made by the teacher or by his older students. It was a common practice to bury the bottles of ink in ashes taken from the stove to keep them from freezing solid. Some teachers used a box filled with sand as an anti-freeze storage place for ink. Even lead pencils were a luxury. There was only one in the school taught by Miss Lockwood, and it was constantly borrowed by the settlers in the neighborhood who, according to the teacher, kept it wrapped in paper. The playground equipment used during intermission in the early schools was very meager; often there was none at all. Consequently, simple games like drop the handkerchief, hide and seek, blackman, and dare base were played by the smaller children. Older pupils played shinny [a type of pick-up hockey] and ball. The ball was usually made of string by one of the pupils. Judge W. M. Ryan, of Homer, says that the favorite pastime in the winter was coasting on the snow. Since there were no small sleds for this pastime, the tops of desks, boards, dishpans, and coop shovels were used as substitutes. Many schools held box socials in order to raise money for a school bell, a new blackboard, or any other equipment needed. Sometimes, according to Mr. Sharp, voting contests were held at a penny a vote. The purpose was to determine “who was the most luscious girl in the neighborhood.”

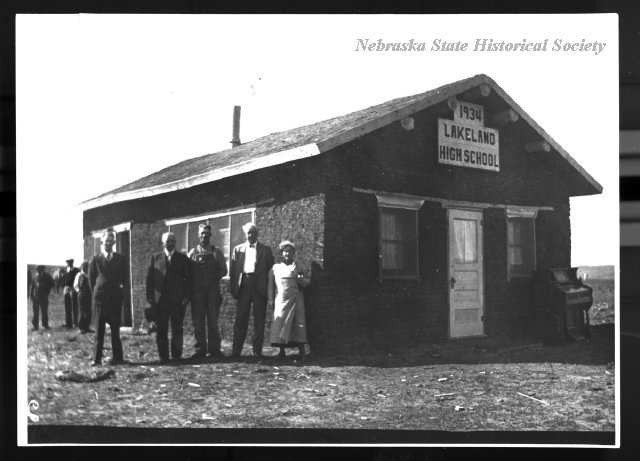

Lakeland sod high school after completion. Community leaders pose for this group portrait at the dedication. c. 1934. RG4290.PH0-001508

Lakeland sod high school after completion. Community leaders pose for this group portrait at the dedication. c. 1934. RG4290.PH0-001508

Textbooks The pupils furnished their own textbooks until 1891 when the Nebraska free textbook law–one of the first in the nation–was passed. Some pupils were unable to furnish any books. The lack of uniformity was the bane of the early teachers. Many of the textbooks had been brought from the East by the parents of the pupils. Mrs. Cornish found six different kinds of readers in a class of eight beginners. A.B. Cornish and Mrs. Cornish, who before their marriage taught in the same county, printedlessons in a small account book given out by a patent medicine concern for one boy who had no book during the first seven weeks of school. The first school in Jefferson County, in 1860-61, did not have a single textbook during the first year of school. The teacher had to substitute as best she could with the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress. Dr. A. A. Reed, who taught school in Gage County in the early ’80’s, says the salesmen, in an attempt to drive a wedge for their particular books, argued that the frequent changing of texts gave the spice of a variety to hum-drum school work by stimulating new interest and effort. After the new books had been installed, the salesman took the opposite side of the argument by saying the school had perfect textbooks so it would now be wisest never to make a change. Such sales sophistry was practiced by book salesmen throughout Nebraska in the ’90’s.

Lakeland sod high school after completion in 1934. People pose for their portrait in front of the new school. RG4290.PH0-001507

Lakeland sod high school after completion in 1934. People pose for their portrait in front of the new school. RG4290.PH0-001507

Pioneer Teachers Some of the young pioneer teachers knew little more than their pupils. They were hired because sparsely settled communities could not afford to pay wages demanded by more experienced teachers, or because they needed the position, or had relatives on the school board. Mrs. A. V. Wilson of Lincoln, tells of an experience she had in Colfax County where she went to school in the ’70’s. The teacher, a young girl whose education had not extended beyond the fifth reader, managed fairly well until she came to the advanced grades where, whenever she encountered any lessons she didn’t understand, she skipped over to the next lesson. When the director visited the school, one of the older boys, who was aware of her real reason for skipping lessons, would invariably appear to get confused, and then, selecting on of these omitted lessons, he would ask the teacher questions about it. She, knowing her limitations, would just as invariably say: “The lesson has been passed over because I don’t think it is important enough for class work.” Nothing was ever done about her lack of knowledge, so the skipping of lessons continued. Discipline was often very poor. Mrs. Herzing recalls one parent saying, when bringing in her unruly youngster, “Remember lickin’ and larnin’ go together.” The life of the early teacher was often far from pleasant. Salaries, when paid at all, were often as low as seventy-five cents and a dollar a day. Nearly always part of the salary was paid by room and board. When this was done, the teacher made the rounds living with the various families of the district who had children in school. The longest time was spent with the families who had the most children. Usually the sod home was so crowded that the teacher was forced to sleep with one of the children. Sometimes the entire family slept in one room. Food was quite a problem. A teacher in Saunders County spoke of being fed nothing but milk and parched wheat in one home of many children. Home-made molasses and corn-bread was another common diet. B.C. Jones recalls that, when teaching in Custer County in 1887, he had so much difficulty in finding a place to stay that for a time he thought he would be forced to sleep out in the open. At one soddy, he shared a bed with two boys, chickens roosted at the foot and pigeons were in the rafters overhead. Finally, he secured a permanent place with a Bohemian family. They prepared his meals American style, while they ate theirs out of one large family bowl. Teaching qualifications were very low in the ’70’s and ’80’s. The passing of the sixth reader was often considered sufficient for a boy or girl to enter the profession. Isabell Cornish tells of teaching school in Custer County in the fall of 1884, when she was fourteen. She came to the school, younger than some of her pupils, wearing short skirts, and with her hair in long braids. Later, dressed as a typical lady teacher of the time, she wore high shoes, a long skirt, a tight waist, and a blouse with long sleeves and a high neck. Her hair was coiled high on her head. Some teachers added a professional touch to their appearance by wearing a white apron in the school room. [1] Arta Ethlyn Kochen’s story is from a Timeline column. Checkout our other blog post about pioneer schools titled “Too educated to teach: Letters from a Nebraska educator in the 1890s” by clicking here.