Ignore the photo above and look at the map below. Is “Great Desert” the dumbest description of Nebraska ever to appear in print? Sure, we’ve all heard “flyover country” and “middle of nowhere”—but desert? We might imagine a mapmaker who hadn’t been within 500 miles of Nebraska.

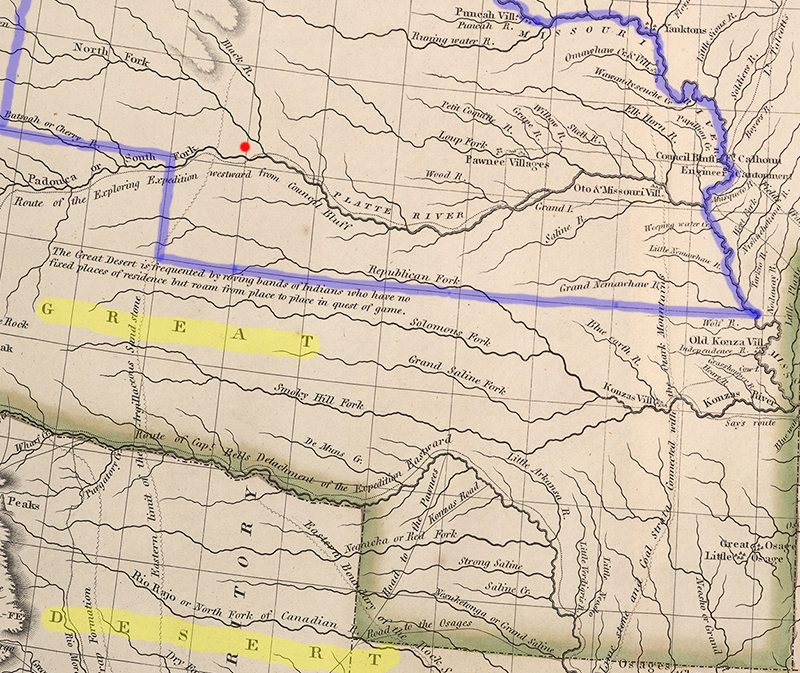

Take a look at this Map of Arkansa and other Territories of the United States (1822):

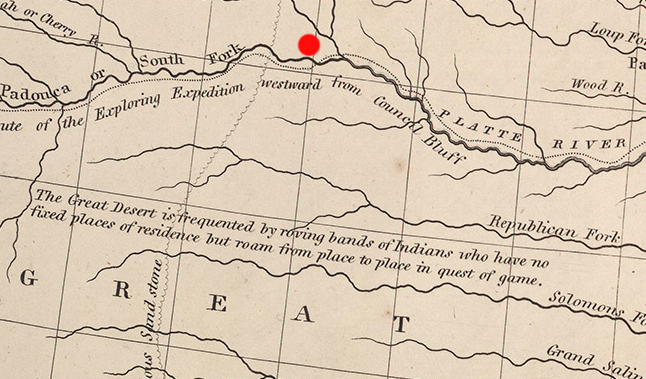

It’s too small to read, so let’s zoom in:

I marked the present boundaries of Nebraska in blue, and highlighted the words “Great Desert.” They appear just south of the present state line. So we’re in the clear, right? Not so fast. Let’s zoom in some more. To keep our bearings, notice the red dot in southwest Nebraska. That’s the present-day city of North Platte:

Just below the Platte River, we read, “Route of the Exploring Expedition westward from Council Bluff.” Just below the Republican River is the inscription, “The Great Desert is frequented by roving bands of Indians who have no fixed places of residence but roam from place to place in quest of game.”

This map was published by Maj. Stephen Long of the US Army. In 1820 he led an exploring party through the “desert” along the Platte River to the Rocky Mountains, then returned east by a more southerly route. The expedition had set out from St. Louis in 1819. They traveled up the Missouri River in a specially-built steamboat called the Western Engineer and built their winter quarters north of present-day Omaha. They called their camp “Engineer Cantonment.” Archeologists have discovered the site. A special issue of Nebraska History tells the story. (Read highlights and table of contents.)

Long wasn’t kidding about the desert. His geographer wrote that the region:

“is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence.”

But what did Long see when he traveled west in 1820, and why did he call it a desert? This is where Long’s map becomes a story about how the meaning of words can change over time.

Consider Robinson Crusoe, the fictional hero of Daniel Defoe’s famous 1719 novel. As Defoe told it, Crusoe was shipwrecked “on a desert island.” But then he tells of Crusoe growing his own food and raising goats in this rather tropical “desert.”

Back then “desert” meant “a wild uninhabited and uncultivated tract.” Today a writer would write of Crusoe being on “a deserted island”—it’s the same root word. But deserted places tend to be so for a reason. People won’t stay where they can’t make a living. By Stephen Long’s time, a “desert” was a place without trees. Long’s countrymen assumed that a land that didn’t grow trees surely wouldn’t grow crops. That’s what past experience told them. (Roger Welsch writes more about this in “The Myth of the Great American Desert” in Nebraska History.)

In other words, Long’s description of the treeless plains wasn’t as crazy as it sounds, but it wasn’t the whole story. A little to the east of the “desert,” Long marked the location of “Pawnee Villages” along the Loup River. The Pawnees had been growing several varieties of corn in central Nebraska for centuries. They planted their crops in spring, hunted bison in summer, and returned to their earth lodge villages for harvest. It was an early version of today’s corn-and-cattle ag economy.

The idea of “The Great American Desert” was the Long Expedition’s most consequential result. It remained on maps for a generation. During that time, political leaders saw the country west of the Missouri River as a permanent home for the Native peoples they were displacing from valuable lands to the east. As Long’s editor, Edwin James, put it:

“Though the soil is in some places fertile, the want of timber, of navigable streams, and of water for the necessities of life, render it an unfit residence for any but a nomad population. The traveler who shall at any time have traversed its desolate sands, will, we think, join us in the wish that this region may forever remain the unmolested haunt of the native hunter, the bison, and the jackal.”

“Forever” lasted about 30 years, but that’s another story.

Oh, and that photo at the top of the page? That’s from the Sandhills in Holt County, Nebraska, during a severe drought in 1936—because sometimes the Great Plains really does behave like a desert in the modern sense of the word.

—David Bristow, Editor