Early airmail pilots flew open-cockpit biplanes, navigating by landmarks and simple maps, and landing in grassy airfields. But by 1930 their facilities and technology had changed dramatically. Kathleen Alonso tells the story in “Trail above the Plains: Flying the Airmail through Nebraska from 1920 to 1930,” in the forthcoming Winter 2018 issue of Nebraska History. Here we present a few photos from that story, plus an excerpt below.

“On January 10, 1930, a plane crashed in a blizzard ten miles west of Sidney, Nebraska,” writes Kathleen Alonso. “In an instant, twenty-eight-year-old Charles Kenwood became the first airmail pilot to lose his life in the state. Kenwood had dropped his two flares in an attempt to locate a landing site, but his efforts failed. Witnesses speculate that he did not realize how close he was to the ground when he crash-landed on the farm of Ben Crouch, leaving a debris field of 200 yards. After a funeral at St. Luke’s church in South Omaha, Kenwood was buried at Graceland Park Cemetery.

“The most incredible thing about the fatal crash is that it had been so long coming, given the myriad of tragedies which defined the beginning of the airmail service. In 1920 alone, nine pilots, five mechanics and other staff, and the newly appointed district superintendent for the Omaha-to-Chicago portion of the route died in the line of duty. The following year the fatalities included James T. Christiansen of Blair, Nebraska, who failed to locate the airport in Cleveland, Ohio, one foggy day. A propeller still tops the Danish immigrant’s gravestone, defining his life as a flier.

“Public outcry and congressional skepticism meant that the fate of airmail in the early 1920s remained uncertain, but by 1930 the well-established aerial trail across the country had become a fact of life. The Air Mail Service took off, survived, and eventually thrived due to the influence of people in power, the determination of its pilots, the vision of community leaders, and the commitment of mechanics and other airport staff on the ground. It also relied on individual farmers, doctors, townspeople, and passersby, who supported local airfields and assisted pilots when mechanical difficulty or weather forced them out of the trail in the sky.”

But how and why did airmail begin when airplanes were still so crude and dangerous? Alonso explains:

“The Air Mail Service, in which Nebraska would become a key player, began between Washington, DC, and New York City in 1918. Almost immediately after its creation Albert Burleson, the Postmaster General, and Otto Prager, the head of the Air Mail Service, pushed to create a coast-to-coast aerial highway with feeder lines from other cities connecting to the existing route. Despite the advancements in aviation during World War I, tremendous obstacles impeded the endeavor. The few airports that existed were little more than level fields. Pilots flew by sight, which made fog or unexpected storms deadly. The Post Office’s route required pilots to fly in open cockpits over treacherous mountains and remote sections of the western United States with no ready help available in the event of an emergency. Despite these challenges the first scheduled mail flew from New York to San Francisco via Cleveland, Chicago, Omaha, Cheyenne, Salt Lake City, and Reno in September 1920. Less prominent fuel stops also developed airports to aid the pilots.

“A series of radio towers linked these cities and towns, allowing airports to communicate with each other regarding weather and the expected time of arrival for pilots. Soon after their installation, the new technology began providing non-aviation messages for the benefit of the local population. For example, in February 1921, William Votaw, manager of the Omaha airfield, received permission to transmit wireless weather reports to farmers in western Nebraska and eastern Iowa.

“In 1921, the Post Office feared that Congress, with the support of the new Republican President, would cut funding for the fledgling service. The Post Office responded with a publicity stunt of epic proportions. That February two planes set off from each coast in an attempt to fly the mail nonstop across the country, rather than transferring it to trains when darkness fell, the usual course of action. One eastbound pilot died in a crash over the Nevada desert, and fog kept both westbound planes from leaving Chicago. Pilot Jack Knight became a national hero by flying from North Platte all the way to Chicago when weather prevented his relief pilot from reaching Omaha. Towns lit bonfires along the way to help keep him on course. Front page headlines touted the success, and the wave of positive publicity became a huge asset for the new service. This, along with some Washington politicking, kept the service going.”

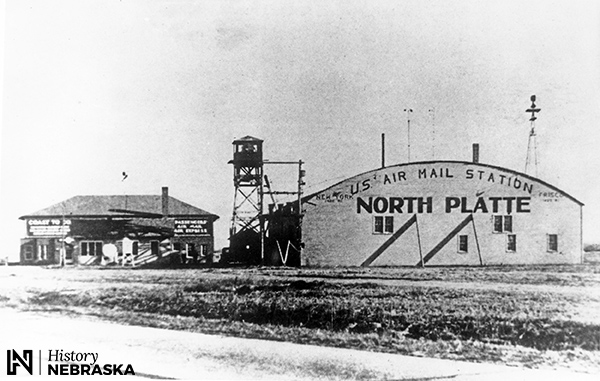

Undated photo. HN RG2929-148

“The Post Office’s next step for improving the speed of delivery meant developing a strategic plan for permanent night flying, which involved a series of light beacons placed ten to fifteen miles apart between Cheyenne and Chicago. These would later be extended across the country. Pilots started testing the practicality of night flying in February 1923 by making twenty-five-mile flights in and out of North Platte. Kerosene lamps marked the Platte River, which bordered the south edge of the field, and staff set up two bonfires to mark where planes should land. A highly successful nationwide test run followed in August. For five days the mail left California in the morning, reached Cheyenne by nightfall, and Chicago by the following morning. The regularly scheduled night service began on July 1, 1924.

“In September 1924, the United States Air Mail Service division, led by Carl Egge, relocated to the Federal Building in Omaha. Egge started his career as a postal clerk in his hometown of Grand Island before becoming a railroad postal clerk in Omaha. He worked his way up to postal inspector in Minneapolis before joining the Air Mail Service. The head office remained in Omaha only a short time before returning to Washington, DC, in July 1926.

“The Post Office airmail pilots did not regularly carry passengers, although occasionally an official or other individual received special permission to ride along in the extra seat. World War I Ace Eddie Rickenbacker crashed at the Cheyenne field en route to Washington, DC, in May 1921, hitchhiked to Omaha with airmail pilot Christopher Pickup, and jumped in William Hopson’s plane to reach Chicago. The development of private airlines allowed passenger service to really take off.

“By 1925, commercial aviation had begun to catch up with the Post Office. Congress then passed the Kelly Act, allowing the Post Office to contract airmail services to private corporations. The feeder routes that ran into the main transcontinental artery became the first to be transferred, but it did not take long for the Post Office to completely extract itself from the business of aviation. In 1927 Boeing took over the transcontinental route from San Francisco to Chicago, including Nebraska. Boeing’s passenger service later became United Airlines.

“Airlines also bid for new routes. Universal Airlines instituted Nebraska’s first route off of the main line when they began flying from Omaha to Saint Louis via Kansas City in May 1929. Although this company lacked the longevity and prominence of Boeing, the new route demonstrated the continued growth of aviation.”

Read the rest in the Winter 2018 issue of Nebraska History. Members receive each issue. Single copies are available through the Nebraska History Museum.

Left photo: De Havilland DH-4 airmail planes at Omaha’s Ak-Sar-Ben Field near 60th and Center streets, ca. 1922. The DH-4 was a British two-seat light bomber during World War I; the US Army Air Service also used them, and the Post Office modified them for airmail service. HN RG3882-263-a

Right photo: A Boeing 80A at Omaha Municipal Airport, June 5, 1930. Mayor Richard Lee Metcalfe stands in center. Boeing Air Transport (today’s United Airlines) took over airmail flights in 1927 and introduced its tri-motor Model 80 the following year. More than an airmail plane, the 80A carried eighteen passengers in its heated, leather-upholstered cabin, where a stewardess attended to their needs. HN RG 3882-1-25-1