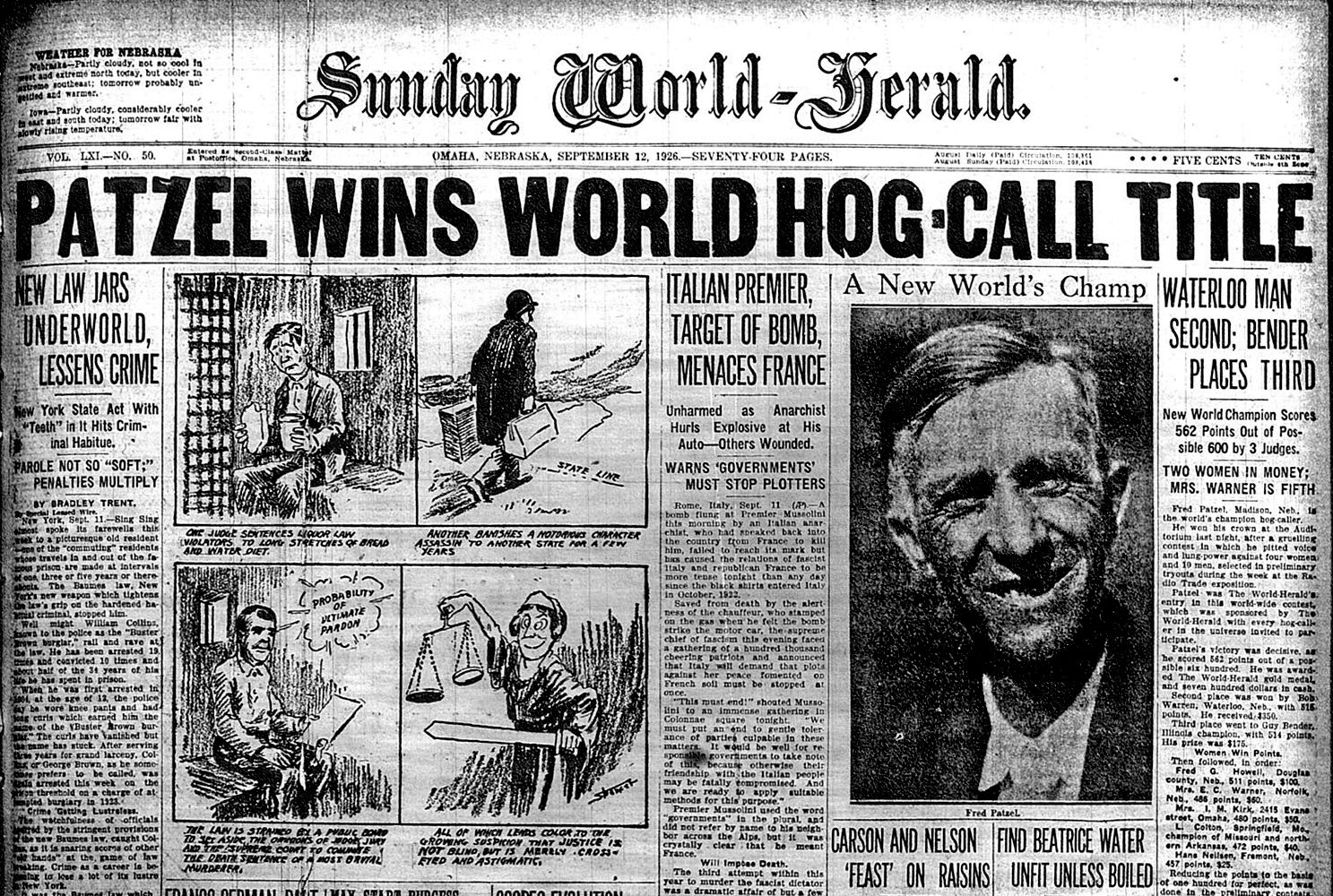

When his last dynamic “Poo-ey” died away at the Omaha Auditorium on the night of September 11, 1926, Fred Patzel had won the title of World’s Champion Hog Caller.

By James E. Potter

Editor’s Note: Historian James E. Potter (1945-2015) wrote and published many articles and books during his lifetime, but we think this article from HIstory Nebraska’s files is published here for the first time (1/3/2022).

When his last dynamic “Poo-ey” died away at the Omaha Auditorium on the night of September 11, 1926, and wafted over the radio airwaves to any of the thirty million Midwestern hogs who might have been tuned in, Fred Patzel had won the title of World’s Champion Hog Caller. His call was described as “a smooth, musical, but sweetly insistent command, rising in pitch and volume which, the judges agreed, no pig could resist.” Fred himself described his technique as giving “the first call as an introduction, the second as an invitation, the third as an order, and the last several as a punch on the flanks of any lazy animal that may be immersed in the mud somewhere out in the hills.”

The competition, sponsored by the World-Herald and the Omaha Radio Trades Association, drew 6,000 spectators and a radio audience of unknown proportions. Patzel, a farm worker and ditch-digger from Madison, Nebraska, received the World-Herald’s gold medal and a check for $700. He had bested forty-nine callers, including six women, from Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Alabama, Arkansas, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia in a week-long competition.

“I can get my teeth fixed now,” said Fred, “and I may buy a few shoats and maybe a milk cow. . . I never got past the second grade in school and I reckon I had better fix things so the wife and children will have a good living. If you got one of these telephones around here,” he said, “I believe I’ll telephone Madison, my home town, that I won. I told my wife when I left home that I would, but she was just a little doubtful.”

Fred’s fame would not be confined to the Corn Belt. New York newspapers announced his triumph, and the Oct. 9, 1926, issue of Literary Digest told his story and published a musical notation of the famous call, said to have been provided by the champion himself.

More was to come, however, when Fred’s hog-calling prowess earned him mention in a 1927 short story by the English writer P. G. Wodehouse. The story, entitled “Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey!” tells of a prize-winning Berkshire sow, the Empress of Blandings, who had gone off her feed when her keeper got thrown in jail following a birthday binge at the local pub. The pig’s owner, the Earl of Emsworth, had exhausted all avenues to insure that the Empress might be restored to her former rotundity, described as resembling a captive balloon with ears and a tail, in time for the pending Shropshire Agricultural Show. James Belford, a young Englishman who had just returned from America, where he had worked on a Nebraska farm, provided the solution. “I imagine she is missing [the pig man] and pining away because he isn’t there. . . She probably misses his evening call.” Belford went on to tell Lord Emsworth that pigs are temperamental and hog-calling is one of the first things you learn on a farm. In fact, he said, “I’ve studied under Fred Patzel, the champion. What a master. I’ve known pork chops to leap from their plates when that man called ‘Pig-hoo-o-o-o-ey.” Belford then demonstrated Fred’s call to Lord Emsworth.

There’s more to the story than that, of course, but in the end Lord Emsworth and his butler learn the call, and with Belford’s help, entice the Empress of Blandings out of her sty and back to her trough. Following the restoration of her hogly appetite, she went on to take the silver medal at the Shropshire ag show.

Fred returned to Madison after his great triumph in Omaha and resumed work as the town handy man. “No sewer ever ran backward if he dug the ditch,” recalled an acquaintance, and of the graves he dug in the cemetery, “families were consoled with the thought that their dear ones lay straight, level, and true in their perfectly sculpted graves.”

Fred Patzel lived in Madison for the rest of his days. His hog-calling prowess was still intact in February 1933 when announcer Karl Stefan invited Fred to lend a little atmosphere to the noon market report on Norfolk radio station WJAG. Fred cut loose and, as the Norfolk Daily News put it, “the famous calls were so loud they overloaded the broadcasting lines and blew out more than $200 worth of tubes,” putting the station off the air for three minutes. “The engineer had not set the broadcasting apparatus to handle the vocal charge.”

As far as we know, no monument to Fred Patzel stands in Madison and when a new pork processing plant opened there in 1967, the idea to name it “Patzel’s Memorial Pork Packery” was turned down. When Fred died on April 27, 1956, his obituary in the Madison newspaper made no mention that he had once been the world champion hog caller. It said only that he had worked in the excavating business for most of his life.