As a commander of US forces, Gen. John J. Pershing was to be a major contender for the 1920 Republican presidential nomination, but his Nebraska-based campaign failed badly.

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

As World War I came to a close, some political insiders counted on a longstanding US tradition—that each major war produced a general who became a president. As a commander of US forces, Gen. John J. Pershing was expected to be a major contender for the 1920 Republican presidential nomination. Instead, Pershing’s Nebraska-based campaign failed badly.

As World War I came to a close, some political insiders counted on a longstanding US tradition—that each major war produced a general who became a president. As a commander of US forces, Gen. John J. Pershing was expected to be a major contender for the 1920 Republican presidential nomination. Instead, Pershing’s Nebraska-based campaign failed badly.

So where did he go wrong? In “Pershing Won’t Do: The Soldier Vote and the Election of 1920,” an article published in the Nebraska History Magazine’s Summer 2021 issue, Bradley M. Galka looks at soldiers’ attitudes as a probable cause for Pershing’s lack of popularity among voters.

The New York Times published an article in November 1918 headlined “Pershing for President in 1920.” Though his candidacy was uncertain, the article crystalized the public’s assumption that he’d run for president.

This would change months later.

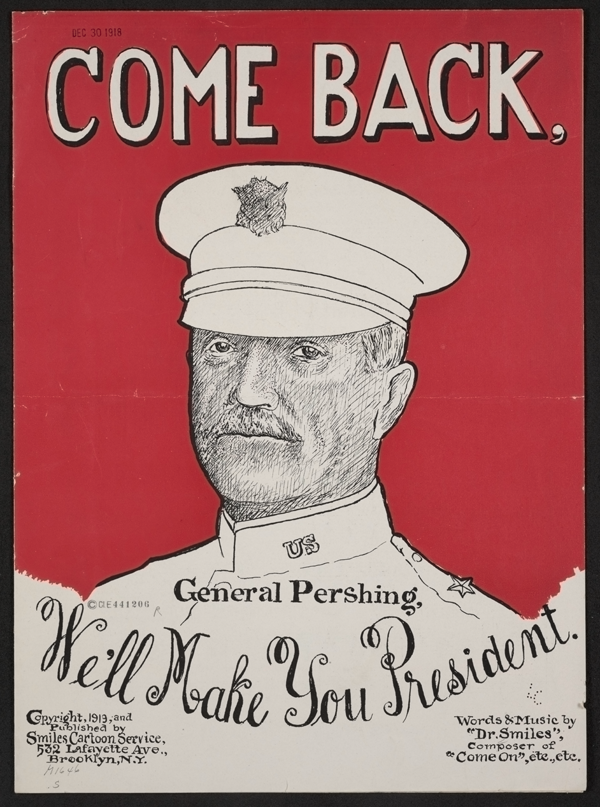

(“‘Come Back, General Pershing, We’ll Make You President’: Song Written by lyricist ‘Dr. Smiles’ encouraging Pershing to run for President. The lyrics note that Washington and Grant made great presidents after they returned home from war, and that Pershing would, too, if only he would run.”)

As the 1920s seemed bound for difficult, complex issues, the nation grew more interested in voting for a qualified candidate rather than handing Pershing the position as a token of military appreciation.

Historian Richard Faulkner examined thousands of soldiers’ letters from the First World War, noting that a vast majority of the lasting impressions Pershing made on his troops happened during demobilization rather than the war itself. As the troops waited for months to be shipped home, Pershing ordered them to proceed with drill and training as if there was still a war to be fought. Soldiers resented this.

Charles Phelps Cushing, a Marine Corps veteran at the time and the co-founder of the American Expeditionary Force’s official news organization in France, wrote an opinion piece describing the feelings of US soldiers for their Pershing. He found that troops lacked affection for their commander due to his actions and approach.

Pershing was the epitome of his generation’s idea of a military man. His army was organized to function as a well-oiled machine, but to his troops he seemed cold and distant. While soldiers displayed “modern efficiency,” Pershing “chopped the heads of hundreds of the in-efficient.”

“As a candidate, one of [Pershing’s] more arduous tasks would be to overcome the antipathy of over two million overseas veterans who had become voters,” a Lawrence Leo Murray was quoted as saying. Unfortunately for Pershing, it was a battle he was not positioned to win.

According to Cushing, servicemen returned home with no intent to vote for Pershing nor any military officer in the election, including Pershing’s rival, Gen. Leonard Wood. While most war veterans had no interest in voting either man into office, between the two, Wood was the preferred candidate. Wood had been denied a major command in World War I, but he was still regarded as a hero for his role in the Spanish-American War and was a much stronger contender at the 1920 Republican National Convention than Pershing.

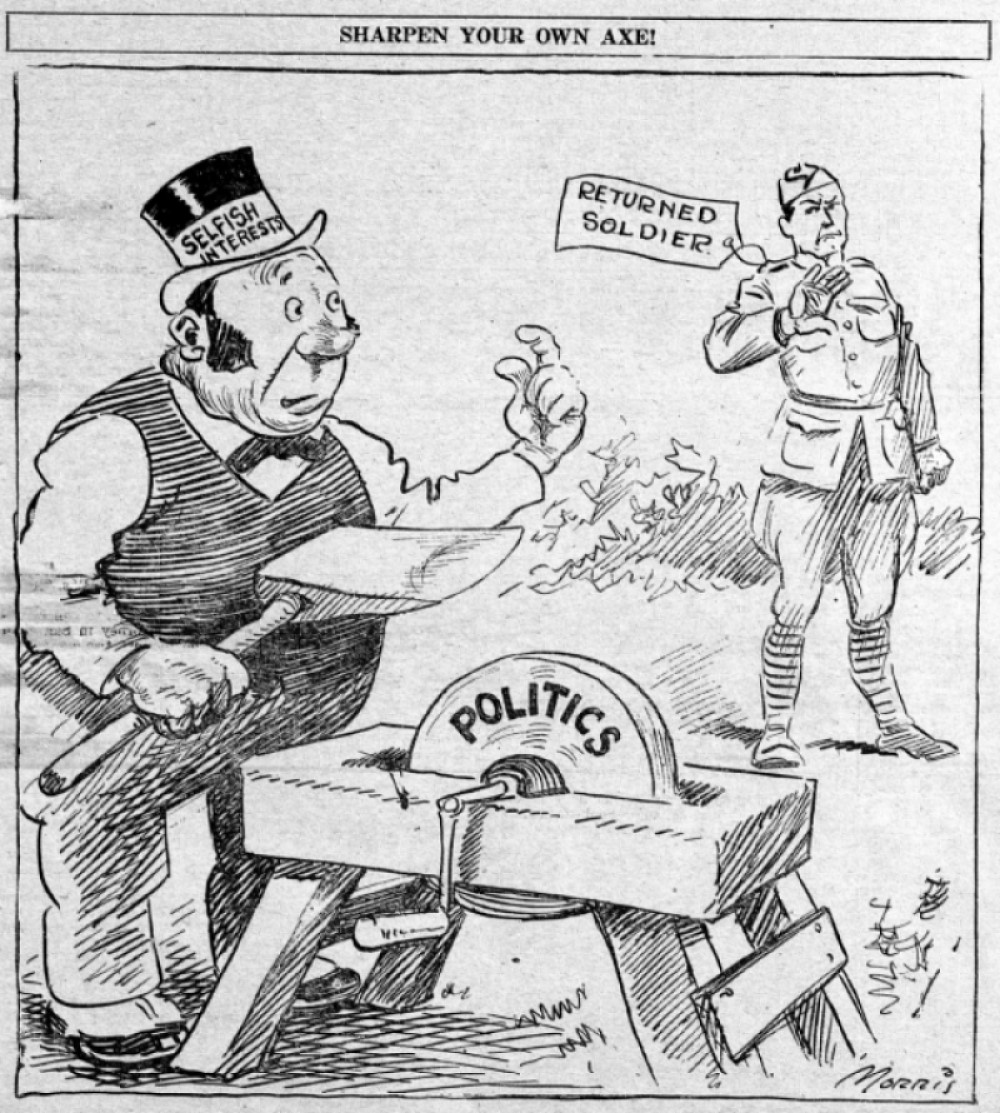

(“‘Sharpen Your Own Axe!’ Political cartoon depicting a U.S. veteran rejecting the advances of ‘selfish-interests’ to sway his vote. Illustration by W.C. Morris.”)

Pershing’s bad reputation was not the only factor playing against him in the election.

As part of his campaign plan, Pershing intended to distance himself from politics and deny his status as a definite candidate. Because he knew he wouldn’t enter the convention with majority support, he planned to present himself as a “dark horse,” a compromise candidate. This entailed staying out of the official convention until the last second where he’d be portrayed as the reluctant but willing candidate to fulfill the nation’s needs.

The focus of Pershing’s strategy was his adopted home state, Nebraska. (Pershing lived in Lincoln in the 1890s.) The campaign’s success depended on the state’s voters to deliver a win in the primaries so that Pershing would enter the convention with at least some pledged delegates. (Most states did not have primaries at this time.) Assuming Nebraskans would patriotically vote for Pershing, he stood a chance at what was expected to be a deeply divided convention. But without Nebraska’s votes, his run for office would be over.

(Pictured Right: History Nebraska 7104-388-(29))

By the time Pershing officially began his campaign efforts, however, it was too late. Wood gained the loyalty of most of the state’s Republican Party Leadership.

Pershing’s poor performance was due to several factors. He began his campaign late after a long period of acting like he wasn’t interested. The combination of his unpopularity among troops, lack of personal appeal, and his bad political organization ultimately guaranteed his loss.

The entire article can be found in the Summer 2021 edition of the Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues per year.