Those wishing to eat away from home in Omaha in 1886 had a wide variety of restaurants, cafes, and lunch counters to choose from. The Omaha Daily Bee on August 29, 1886, reported that eating establishments in the city were “multiplying thick and fast. There is scarcely a block in the city that has not one or two of them.”

The Bee said: “There is a well-known establishment on lower Douglas street which leads all other restaurants in the city. It is finely furnished, large fans suspended overhead keep the patrons cool, obliging and attentive waiters are ready to obey every behest of the hungry customers. . . . There are other good restaurants in the city which do a business almost as large as the one mentioned above. Some of them sell meal tickets for $4, some for $4.50 and some for $5. These meal tickets are generally good for twenty-one meals and expire in ten days.”

Another popularly priced restaurant near Fifteenth Street and Capitol Avenue, was operated by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which used the proceeds for its temperance and charitable work. “Prices were put down to a low notch,” the Bee said. “A cup of coffee (first class, too) was listed at five cents, sandwiches the same, pie the same. Nearly every order was placed at a nickle [sic]. Twenty-five cents would buy a square meal. Patrons came and the business flourished. . . . Finally some of the ladies abandoned the idea as a means of furthering the ends of charity, left the parent institution, and in various parts of the city opened up rival restaurants as a purely speculative venture. All have succeeded well and are now making money.”

Inexpensive lunch counters were springing up all over the city. High stools were ranged beside counters covered with white oilcloth, on which the meals were served. “Here, too, the five-cent prices prevail. . . . Closely akin to the last mentioned class of restaurants are the lunch counters which are to be found in many of the saloons of the city. In the best of these one can find anything from a ham sandwich to the most elaborate meal, costing seventy-five cents or a dollar. Many of these places are making money, and making it rapidly, too.

“Some of the hotels, while they cannot, strictly speaking, be classed as restaurants, yet do a restaurant business and secure quite a large slice of trade. Most of them sell tickets for $4 or $5, good for twenty-one meals, and limited to use within ten days. And again, there are innumerable other places where meals are advertised even cheaper than in the places mentioned above as low as ten or fifteen cents.”

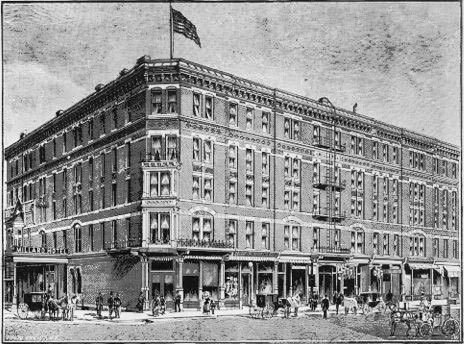

Omaha’s Millard Hotel at Thirteenth and Douglas was said to have a culinary department “under the management of O. N. Davenport, a steward who has made the Millard famous throughout the west.” From Omaha Illustrated (Omaha, 1888).