Police arrest BLAC sit-in protestors, November 7, 1969. – Tomahawk 1970 yearbook, 65.

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

African American students fought to seize their “educational destiny” in the 1960s, but history has been slow to acknowledge those efforts and amplify their voices. UNO’s double standard regarding the exclusivity of Black and White student organizations is a telling example of this. Brent Ruswick and Celine Butler explain UNO’s 1960s racial politics in “No Mutually Acceptable Solution: The Struggle to Integrate Campus Life at the University of Nebraska-Omaha,” in Nebraska History Magazine’s Fall 2021 issue.

Activism in the Midwest was “gradual and somewhat ‘winding’” compared to more populous areas. Like many campuses, UNO’s student body was integrated within classrooms but not outside of them.

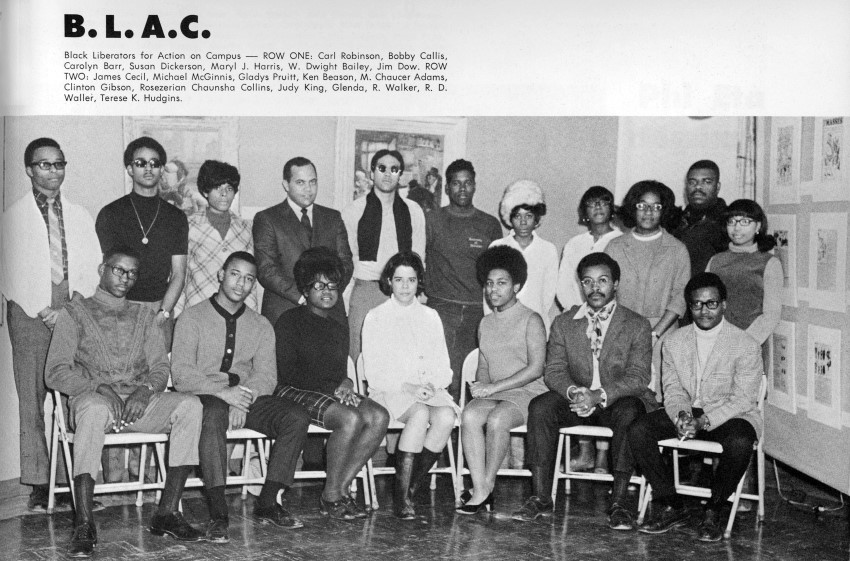

Recognizing UNO’s lack of diversity, a group of students applied for the creation of BLAC (Black Liberators for Action on Campus). The organization’s purpose was to “promote better representation” on campus and give Black students a chance to build close relationships.

Despite BLAC’s good intentions, they received pushback in 1969 when the Board of Regents thought their constitution was racially exclusive. The constitution stated that membership was open to anyone “sincerely interested in promoting the purpose of this organization,” and the board asked that the language be revised.

University of Nebraska Omaha president Kirk Naylor. – Tomahawk 1969 yearbook, 34.

After some discussion regarding the unlikelihood of White students joining and the objectives of the organization, they received approval. The university appeared indifferent toward BLAC.

That was short-lived.

When BLAC hosted a dance on campus, they requested a Black security officer and ticket taker. The university’s social director declined. They were instead provided with an all-White staff, and a single record player without any speakers.

Seeking reimbursement and the resignation of the administrators involved, 50 BLAC members quietly marched to UNO President Kirk Naylor’s office. President Naylor agreed to a formal meeting, but told reporters there would be no negotiation.

In response, BLAC’s president announced that students would occupy Naylor’s office until their demands were met.

The authorities were then called, arresting 40 students for “unlawful assembly” and filing 54 felony charges against protestors.

President Naylor said he opposed discrimination but needed more evidence before he took action. Many students disagreed, believing the administration maintained systems of discrimination on campus.

Steve Wild, president of the Student Senate, criticized the incident and used it as an opportunity to advocate for the senate’s influence on campus. Wild argued that the senate should be “the supreme governing body to which all student grievances must initially be present.” He speculated that if it functioned this way, the incident would’ve been prevented.

Wild’s predecessor thought that if the senate had “the power to regulate and supervise all student organizations,” as stated in their own constitution, that they had a right to review all constitutions. So in the spring of 1968, they requested constitutions from all student organizations for review.

By the time BLAC’s constitution was finally approved by the senate, half of the fraternities and none of the sororities had even submitted theirs.

BLAC membership. – Tomahawk 1969 yearbook, 113.

Greek life dominated student government and, being almost exclusively White, symbolized the administrators’ acceptance of organizations founded on racial exclusion.

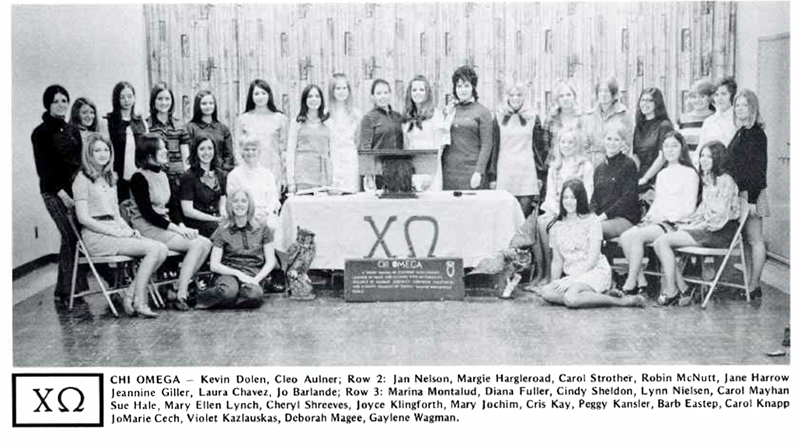

The most popular sorority on campus, Chi Omega, insisted on keeping their national constitution private. They wanted to protect other campus chapters where “such information may be used unwisely.” This was in reference to the “mutual acceptability” clause in their charter, which required that new pledges be acceptable not only to the local chapter, but also to other chapters across the US. It was believed that all-White southern chapters would not approve of Black women joining the sorority.

In 1971 the Board of Regents demanded that all student organizations from all three campuses in the Nebraska system send their constitutions for review of “discriminatory and other unhealthy clauses.”

The Zeta Deltas wanted to revise their national constitution. However a national representative’s lecture about “mutual acceptability” indicated that they’d lose their national charter for pledging an African American.

Some members promptly resigned, and an investigation began shortly after.

On May 20, the student senate affirmed that the national representative led the sorority to conclude they’d lose their charter. The committee contacted the sorority’s national office to clarify whether this interpretation was correct, but they received inadequate responses. The letters did not define “mutual acceptability” nor did they address or resolve the accusations.

The senate voted on June 10 to remove recognition of Chi Omega for the following year. This entailed the chapter losing access to campus facilities until they could provide evidence that they didn’t discriminate on the basis of race.

Chi Omega sorority. – Tomahawk: Summer 1971, 6.

President Naylor acknowledged the situation but refused the idea to suspend the sorority. He sent multiple letters to the representative in hopes of preserving the sorority—an action publicly frowned upon, even by his colleagues.

This second-chance opportunity was a notable contrast to the ten-minute warning Naylor had given to BLAC to clear his office, or his refusal to pardon their felony charges.

Naylor received no response and a resolution was eventually reached: a 15-2 student senate vote in favor of suspending Chi Omega and censuring President Naylor.

UNO’s student body and administration moved on to address other issues, but these events reflect the racial injustices of that time. Between the controversies around BLAC’s sit-in and Chi Omega’s recruiting standards, we can deepen our historical understanding of Midwestern racial politics and student activism.

The entire article can be found in the Fall 2021 edition of the Nebraska History Magazine. Members receive four issues per year.

Categories:

UNO, Omaha, BLAC, racial politics, student activism