Nebraska had its own anti-evolution trial nearly seven months before the famous Scopes trial opened in Tennessee. “Darwin and Genesis fought out a battle in District Judge Broady’s court in Lincoln,” reported the Fremont Tribune, and “Genesis lost and Darwin won.”

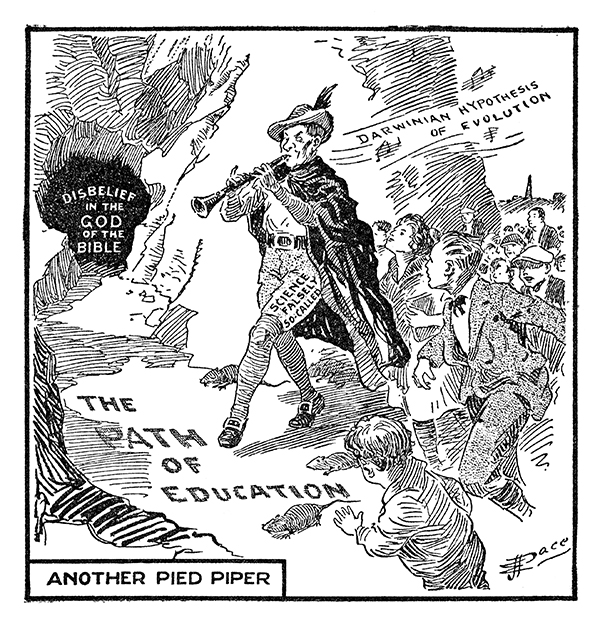

Illustration from William Jennings Bryan’s 1924 book, Seven Questions in Dispute. Though Bryan wasn’t involved in Nebraska’s Domer v. Klink case, Domer’s opponents saw evolution as Bryan did.

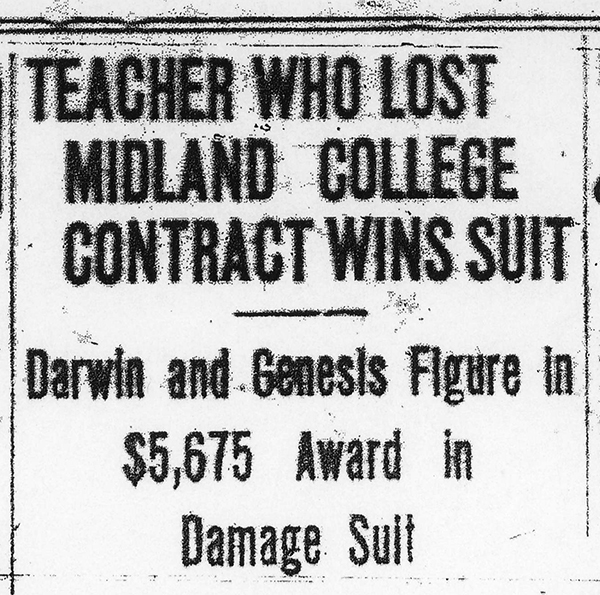

“Darwin and Genesis fought out a battle in District Judge Broady’s court in Lincoln,” reported the Fremont Tribune on October 22, 1924, and “Genesis lost and Darwin won.” Nebraska had its own anti-evolution trial nearly seven months before the famous Scopes trial opened in Tennessee. But how did the Nebraska case remain obscure while the Tennessee case became a national sensation? Adam Shapiro investigates the differences between the trials in the Fall 2013 issue of Nebraska History.

In 1922 Midland College in Fremont, Nebraska, hired Rising City school superintendent David Domer was hired to teach English at at the college. But Domer lost the job after the pastor and several members of a Lutheran church in Rising City wrote to the Midland dean, calling Domer “unfit, morally and mentally” to teach, in part because of his alleged Darwinist beliefs. Domer sued for damages.

In 1919 the Fremont College campus became Midland College. History Nebraska RG3347-2-55

But the case was not as simple as creationism v. human evolution. At least initially, Domer’s lawyers took the strategy of defending his teaching qualifications rather than directly defending Darwinism. Newspapers mostly treated the case as a slander trial. And yet it seems certain that Domer’s beliefs were also on trial, since apart from them there was little of which to accuse him. Domer won the suit and was awarded $5,675 in damages.

Fremont Tribune, Oct. 22, 1924

The case faded away quietly after the local newspaper reports. However, the following year when Tennessee’s Scopes trial became a national sensation, newspapers around the US noted that an evolution trial had already taken place in Nebraska, “and Darwin won.” The New York Times said, “Nebraska … is not the South. It has a warmer welcome for new ideas.” Meanwhile the Fremont Tribune lamented that the state might have been in the national spotlight instead of Tennessee.

“There’s a stark contrast between the public spectacle that took place just nine months later with the Scopes trial in Tennessee and this earlier case that had much the same potential,” Shapiro writes.

This suggests that there were important differences in the way that the evolution controversy was understood in Nebraska in 1924 and Tennessee in 1925 and that the trope of an “evolution trial” as a convenient way to understand these cases (and the many that have come later) is not unchanging. Indeed, the anonymity of Domer v. Klink et al. shatters one of the pervasive myths about the later Tennessee trial. In 1925, participants in the Scopes trial and the journalists reporting on it tended to describe the trial not in terms of the local politics of peculiarities of Tennessee, but as the natural expression of an unavoidable conflict between Darwin and the Bible. They gave the impression that the epic debate between science and religion had to turn into a great public debate. Even though the Scopes trial’s creators went out of their way to promote the event, and celebrity figures like Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan coopted the court case in order to engage in a public debate, there was still a consensus, forged by that trial’s creators, that the media attention and the spectacle were inevitable.

Read the complete article here.

(updated 2/18/2021)

For further reading: Stephen Jay Gould, “William Jennings Bryan’s Last Campaign” (Nebraska History, Fall/Winter 1996).