Historians long believed that in 1541, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado became the first European explorer to reach the Platte River in Nebraska. By the 1890s, historical and archeological evidence pointed toward central Kansas as Coronado’s farthest north, but the story lived on in popular culture.

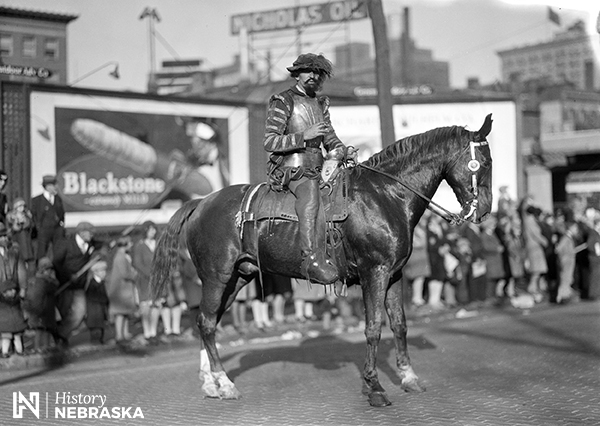

Here, “Coronado” takes a smoke break at Nebraska’s Diamond Jubilee in Omaha on November 5, 1929. The celebration marked seventy-five years since the opening of Nebraska Territory to Euroamerican settlement. More than 150,000 people lined the two-mile route of the “Parade of Nations.” According to the next day’s Omaha World-Herald, the turnout was nearly as large as the record crowds for Woodrow Wilson and Charles Lindbergh.

The parade included Indians representing “Nebraska’s first families,” and floats representing various immigrant groups and historical topics. The parade’s larger theme, said the World-Herald, was to depict “the perils of the pioneers, the struggles and privations of the early home makers and achievements of the second generation.”

More perils, struggles, and privations were soon to come. The same newspaper includes a full-page ad from The Saturday Evening Post attempting to calm fears after the recent stock market crash: “Wall Street may sell stocks but Main Street is still buying goods. The ticker may slow down but production is going right ahead.” Despite cheerleading from the Post and President Hoover, the nation’s economy plunged into the Great Depression.

As for the Coronado story, historian Harlan Seyfer of Plattsmouth writes about the “Changing Consensus on the European Discovery of the Platte River” in the Summer 2018 issue of Nebraska History. The article has the tongue-in-cheek subtitle, “Figuring out which white guy got to the Platte first,” because of course people had been living along the Platte for millennia before Europeans “discovered” it. Nonetheless, the entry of Europeans onto the Northern Plains had important consequences for everyone involved.

Who was the first? As far as we know, it was a Frenchman named Etienne Véniard, Sieur de Bourgmont in 1714. Two years earlier Bourgmont had married into the Missouria tribe. He learned from his in-laws that the Missouria and Otoe Indians had split up in the 1670. The Missourias lived in the central part of the present state that bears their name; the Otoes lived near the confluence of the Platte and Missouri Rivers in present-day Nebraska.

It was Bourgmont who first used the word “Nebraskiér” in print. It was the Otoe name for the wide and shallow river he visited. It means “flat water.” Other Frenchmen translated the name into their own language and started calling it La Rivière Platte.

History Nebraska members receive quarterly issues of Nebraska History as part of their membership; single issues are available for $7 from the Nebraska History Museum (402-471-3447).

—David L. Bristow, Editor

(Photo: RG3882-35-11-1)

(Since this obviously isn’t the oldest known image of a Nebraska event, what is? Find out here.)