Prohibition was the law of the land by 1920, but the Prohibition Party was still uneasy. As the presidential campaign season got underway, they feared that neither a Republican nor a Democratic president could be trusted to vigorously enforce the new law. Already there were proposals to weaken prohibition by modifying the law to allow the manufacture of light wines and beer.

This 1918 postcard shows evangelist Billy Sunday (left) shaking hands with William Jennings Bryan in Chicago, where Bryan was helping Sunday support local temperance forces in their efforts to prohibit the sale of alcohol in the city. RG802-112-4

This 1918 postcard shows evangelist Billy Sunday (left) shaking hands with William Jennings Bryan in Chicago, where Bryan was helping Sunday support local temperance forces in their efforts to prohibit the sale of alcohol in the city. RG802-112-4

So when the party held its national convention in Lincoln in July, they decided to draft two high-profile candidates: three-time Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan for president, and evangelist Billy Sunday for vice president. Patricia C. Gaster writes about it in the Fall 2014 issue of Nebraska History.

The choice of Lincoln for the convention city made a lot of sense. Gaster writes:

The city had a number of advantages. It was centrally located between the two coasts, with good railroad connections, and had a reputation of being friendly to temperance. The large number of churches had in some circles earned it the nickname “The Holy City.” It was the home not only of the University of Nebraska, but of several religious colleges in its suburbs: Nebraska Christian University (Cotner College), sponsored by the Christian (Disciples of Christ) Church, in Bethany; Union College, sponsored by the Seventh-day Adventists, in College View; and Nebraska Wesleyan University, Methodist, in University Place. All three of these denominational schools, especially Nebraska Wesleyan, favored temperance. At Wesleyan few national issues, other than presidential campaigns and the coming of World War I, surpassed on campus the fervor in support of prohibition as dry campaigns to amend the state and national constitutions unfolded in the late 1910s.

The convention was lively. The most memorable demonstration occurred when a member of the Missouri delegation

with a shout grabbed the Missouri standard and jumped into the aisle[;] the delegates grabbed their state insignias and started the march of jubilation. . . . Every state took part in the parade and very few individual delegates held back. The delegates pounded on the floor with the end of the standards and howled ‘We Want Bryan,’ ‘We’ll win with Bryan,’ and ‘Watch the prohibitionists sweep the country.’ . . . A steam roller locomotive yell ‘Bryan-Bryan-Bryan’ was introduced and a number of the group took up the shout.

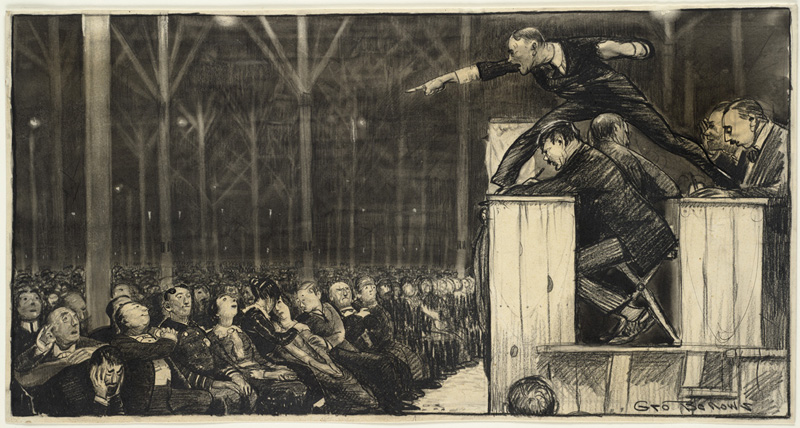

The only question was, would Bryan (who was not present) consent? And what about Billy Sunday? Both men were household names, both were master orators. Bryan is remembered for his “Cross of Gold” speech that electrified the 1896 Democratic National Convention. Sunday drew enormous crowds to his revivals and was noted for his acrobatic and colloquial style of preaching, often standing on a chair or even atop the pulpit while gesticulating at the audience. Both he and Bryan were dead-set against “John Barleycorn.”

This cartoon depicting Sunday’s dramatic preaching style was drawn by George Bellows, and appeared in Metropolitan Magazine in May of 1915. “Preaching” by BPL – originally posted to Flickr as Preaching. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This cartoon depicting Sunday’s dramatic preaching style was drawn by George Bellows, and appeared in Metropolitan Magazine in May of 1915. “Preaching” by BPL – originally posted to Flickr as Preaching. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

You’ll have to read the full article to follow the maneuverings to persuade these two men to run. In the end, Bryan and Sunday declined, the Prohibitionists nominated lesser-known men, and Republicans Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge went on to defeat Democrats James Cox and Franklin Roosevelt in the general election. The article gives a lively and insightful portrait of the temperance movement in the early days of national prohibition.

To learn more about Billy Sunday, see this Nebraska History article about his 1915 “Clean-Up Campaign” in Omaha. (Unlike Lincoln, Omaha was never known as “The Holy City.”) To learn more about Bryan, see the Fall/Winter 1996 issue of Nebraska History; articles are linked from the table of contents (scroll down to 1996).

– David Bristow, Associate Director / Publications