For a short period of time, cattle drives were big business in Nebraska. After the Civil War ended in 1865, growing demand for beef plus a surplus of longhorn cattle in Texas led to thousands of Texas cattle being herded north to Nebraska, where the Union Pacific railroad transported them to the eastern states. Some cattle drives went even farther north, taking beef to Indian reservations in Dakota Territory. Early on, drives brought cattle to eastern and central parts of the Nebraska. Kearney was common destination in the mid 1870s. But as settlement migrated west so did the cattle drives, often ending at Ogallala. By the mid 1880s, the cattle-drive business was already declining in Nebraska, to be replaced by permanent ranches and home-grown cattle.

Here is the transcript of one man’s memories of Nebraska life during the brief cattle-drive years.

REMINISCENCES OF THE DAYS WHEN BOHEMIANS FIRST SETTLED IN KNOX COUNTY, NEBR.

(Translated from an article written by Joseph P. Sedivy, Verdigre, Neb., in Bohemian, for the Bohemian weekly Osveta Americka, in 1911)

In the years between 1870 and 1875 it was the rule that large herds of Texas cattle were driven through our new settlement, each year, beginning in June and ending in September. The cattle was (sic) bought by the government in Texas for the military posts and Indian agencies along the upper Missouri. This wild cattle, with long horns, was in the care of equally wild cowboys, who often dealt roughly with the settlers, causing them loss and endangering their lives.

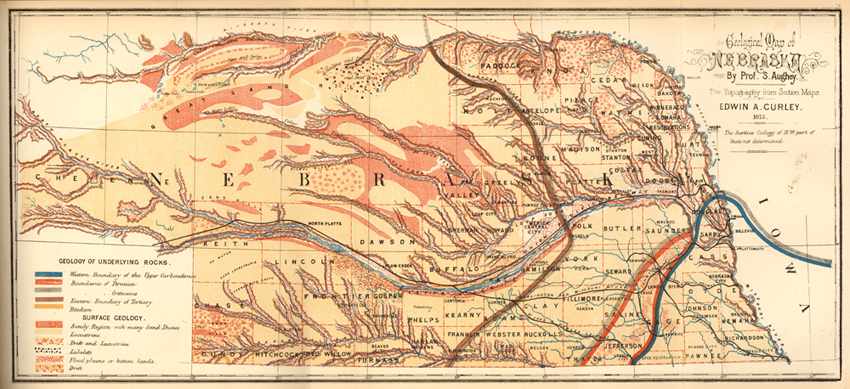

Nebraska, 1875. This map was included in Edwin Curley’s 1875 book: Nebraska, Its Advantages, Resources, and Drawbacks.

Nebraska, 1875. This map was included in Edwin Curley’s 1875 book: Nebraska, Its Advantages, Resources, and Drawbacks.

I remember when a group of cowboys once held a veritable reign of terror in Niobrara and woe to him who refused to do as they bid. For instance, Mr. Frank Janousek had a log house in Niobrara in which he ran a saloon. A crowd of cowboys came with great noise and jumping off their horses, they hastened in. There were about twenty of them. They ordered everything in sight, some paid, some did not. They began to entertain themselves by drinking, playing cards and dice and teasing the proprietor.

When they began to feel pretty gay as a result of too much liquor, those that were playing cards got up a quarrel, just for effect. They pulled out their guns, began to shoot up the place and when the proprietor tried to restore order and demanded pay, they turned their weapons on him and the bar tender. Each of the latter was armed but each realized that discretion was the better part of valor. The proprietor lived in the back rooms, and so he and the bar tender made their escape there, barricading the door firmly.

The unwelcome guests sent a few shots after them, then amid general laughter, swearing and singing, they all fell on the stock at hand, and a wild orgy ensued. Revolver shots, an unearthly ding, singing, swearing, breaking glass, etc. resounded far and wide. They used everything for targets, even the bolt on the door. Niobrara was the county seat and the sheriff lived there, but he was afraid to come forth, knowing that he was practically helpless.

All the houses were fortified in various ways and the occupants trembled with fear. The men were armed and prepared to defend themselves and families. The racket lasted until dark, when a few sober cowboys came from the camp and with great difficulty got the rest to go with them. The camp was situated about two miles from town, but the quiet air during the whole night was rent with din. Mr. Janousek received no damages for his loss. This was but one example of what the cowboys used to do.

It was their custom, when driving a large herd, often numbering ten thousands, to take it across the vast prairies in somewhat the following order: the boss cowboy rode first with one or two cowboys, then came a herd of healthy stock, driven by cowboys who rode on horses, at the sides. Then came a herd of tame horses, generally led by a docile mare with a bell about her neck. Then came more cowboys, then wagons drawn by three pair of oxen each, with Mexican drivers. The wagons contained the provisions and necessities. Then came a herd of sick and lame cattle, driven by two or three cowboys.

Photos like this one show what cowboy life was like in the late 1800s. Cowboys on Thomas B. Hord’s “77” ranch in Wyoming were photographed at their chuck wagon dinner during the 1880s. RG4232-5

Photos like this one show what cowboy life was like in the late 1800s. Cowboys on Thomas B. Hord’s “77” ranch in Wyoming were photographed at their chuck wagon dinner during the 1880s. RG4232-5

When the herd reached the Missouri valley at Niobrara, which at that time was unsettled, with the exception of the little town and a few farms, the cowboys made camp. It was necessary now to drive all the animals over the Missouri River, to the other side. It was the custom to divide the herd into groups of three and four hundred head each. Local Indian half-breeds were hired to assist. They sat in their boats and helped to steer the cattle over. This was most dangerous work, when an enraged beast refused to go on and attacked the man in the boat. But Indian half breed were good swimmers and brave, and were eager to do the work for good pay. Later white men used to do this work too.

It was interesting to watch a mottled herd of cattle swimming in the river. The weak ones often perished by drowning or stuck in the mud, and such became the prey of Indians loafing on the banks. The red men sat in the tops of trees along the shores like vultures and used every occasion to get the unfortunate animals. When they thus gained a goodly supply of meat, they had a great celebration in the near-by village, from whence could be heard, the whole night long, their racket and din.

It happened also that during storms the cattle stampeded at night and many heads wandered away into the hills southeast of the Niobrara valley. Cows, feeling their hour of pain coming on them, got miles away from the herd. The cowboys did not care much about looking for lost cattle, except when a general stampede occurred. It was the rule that any lost heads became the property of the person who found them, be he white or red, each had an equal right.

“A Drove of Texas Cattle Crossing a Stream,” Sketched by A. R. Waud. Harper’s Weekly, October 19, 1867

“A Drove of Texas Cattle Crossing a Stream,” Sketched by A. R. Waud. Harper’s Weekly, October 19, 1867

I often helped to get such an animal and I could relate many an interesting episode of such occasions. But I will limit myself to one, which happened toward the end of September 1872.

I was but a boy at that time and it was my duty to look after father’s cattle, consisting of a pair of oxen, two cows and a heifer. In those days cattle roamed at will, for but a small share of the ground was under cultivation. The cattle usually came home at night by itself (sic), and if it did not, we had to get it.

I started out one evening to get our stock, but could see no signs of it, nor hear the bell. I took myself over the hills to the east until I came to a little creek that flows into Sturgis Creek. The sun was nearly setting and I could not find the cattle. I decided to go down to the creek and if I did not find anything, to return. I was about three miles from home. I started to cross the hill, to get to the creek, but when I reached the top I saw a large Texas steer lying there in the valley. I knew it was dangerous to approach him on foot, so I retraced my steps as quietly as I could. I hurried for help and wanted to get the steer before darkness came on. Mr. John Barta lived on his homestead on Vertigre Creek and was he was a good huntsman, I turned to him.

When I got to his dug-out and told him my mission, he was ready in a minute. Before we reached the place where I had seen the steer, twilight came on and it was necessary to go ahead carefully, so he would not see us first. But to our great sorrow he was gone. There were three of us, Mr. Barta with his trusty gun, Mr. J. H. with a knife and hatchet and I with my weapon.

Suddenly we heard a noise in the grass and we saw in the dark a black object. I was greatly excited and fired twice and my shots started up several other black objects. We all sped after them, when Mr. Barta cried: “Be careful!” and there we saw, about thirty feet away, our “boy from Texas.”

At the same time a dreadful odor spread around us which we knew to come from skunks and so we began to retire hastily, especially since the long horn showed signs of impatience. Mr. Barta took a shot at him, the animal reared and it seemed was struck. It took several wild jumps, as it seemed in our direction, and we ran as fast as we could, although we were well nigh suffocated by the horrible stench. I felt myself falling, so I grabbed hold of Mr. J.H. and dragged him with me into a pool. Mr. Barta fell over a log, stopped, and not seeing any danger, called for us.

We got out, I had lost my weapon and Mr. J. H. his hatchet. When Mr. Barta saw us, he had a good laugh. We decided to set out in the morning to look for what we had lost and see if we could not find the wounded steer. I got home tired and chilled, called my father out and told him what had happened. He brought me clean clothing which I put on in the barn, then I went up into the attic without any supper other than a cup of hot, black coffee.

The next day Mr. Barta and I went forth and found our weapons, but aside from a stench nothing was to be seen of the skunks. We found the tracks of the steer and a good deal of blood, and although we followed the tracks for six miles, we lost them in a deep ravine overgrown with high grass. Being hungry and tired we decided to return home. A few days later I met Mr. J. H., but he was minus his beautiful, blond beard. When I asked him why he parted with it, he replied that he was obliged to on account of the smell. He swore never again to look for lost Texas steers.

– Joy Carey, Editorial Assistant, Publications*

*Special thanks to Marty Miller of the reference staff for bringing this memoir to our attention.