The Omaha Public School District was forced to face its racial imbalance and produced an integration plan that would reassign students to new schools and bus routes.

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

In 1975, the Omaha Public School District received a court order to integrate its schools.

While racial segregation was not an official school district policy, it was a result of the city’s long history of housing discrimination.

The racial imbalance was addressed in a 1974 US District Court case, but action wasn’t required until the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals issued its order a year later.

The school district was required to submit a “comprehensive plan” by January 1, 1976, providing a fair integration ratio of Black to White students and faculty while fulfilling the court’s guidelines. It would then be implemented that fall.

Omaha World-Herald, June 13, 1975

Other cities across the nation received court orders as well, reassigning students to other schools and implementing complex busing arrangements. These plans often faced violence and white flight.

Omaha residents knew about the court order, but didn’t know what expect.

The court order came as a shock to Owen Knutzen, the Omaha Public Schools’ superintendent, who hoped to voluntarily integrate the schools. He feared that the court order would create conflict and white flight to suburban school districts.

In the following months, there was no definite evidence of white flight. Local real estate agencies noticed more people taking interest in homes outside the Omaha School District, but few made actual purchases. However, they also noticed that fewer outside buyers were moving into the district, opting for homes in suburban districts instead.

Many residents thought suburban school districts should’ve been included in the integration plan and felt that they were isolated from the issue. If they were included, “Maybe the suburban districts [would] change their attitude of ‘it’s your problem’ and help us fight this ridiculous infringement on our constitutional rights,” a local man wrote to the Omaha World-Herald.

Parents widely disapproved of their children being transferred to schools outside of their neighborhood for reasons other than convenience, use of better facilities, or special education needs. One parent wrote, “Without a vote being cast, someone has taken from the parent the right to choose a public school and the right to prevent his child from being taken out of his immediate neighborhood.”

Residents also feared possible protest demonstrations and worried about children’s safety.

The school district took the public’s concerns into consideration and tasked a board of members with formulating an effective integration motion.

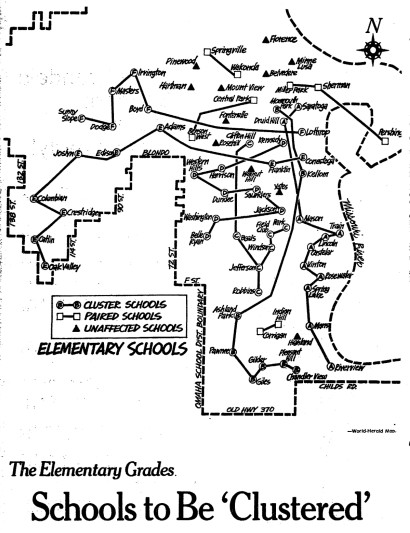

A plan was presented in December 1975, reflecting specific implications on elementary schools, junior highs, and high schools.

Omaha World-Herald, Dec. 15, 1975

Elementary schools were the most impacted as they were separated into “clusters” among which students would be dispersed. Junior high schools only required the reassignment of specific attendance zones and grades, and high schools were the least affected. Of the eight Omaha high schools, four were already considered integrated. The school district hoped that students would voluntarily transfer to assist the balance efforts, but were prepared if there weren’t enough transfers.

To reinforce this integration, students would also be assigned to new bus routes with their peers.

People debated the effectiveness and benefits of busing students. Some questioned whether it would be helpful for integrating students or expressed concern about its impact on quality of education. State Senator Ernie Chambers, in a letter to the mayor, argued that “the only way to effectively eradicate segregation is to place white children in black schools and black children in white schools. Busing is the only tool.”

A group of seven Black parents also responded to the plan with doubts. Calling it “salable,” they thought the plan was heavily influenced by the officials’ need for White acceptance and their fear of white flight.

“It was conceived to solve the ‘dilemma’ of how to get White students to inner city schools. It was conceived assuming that Black parents will accept desegregation on any terms,” they wrote.

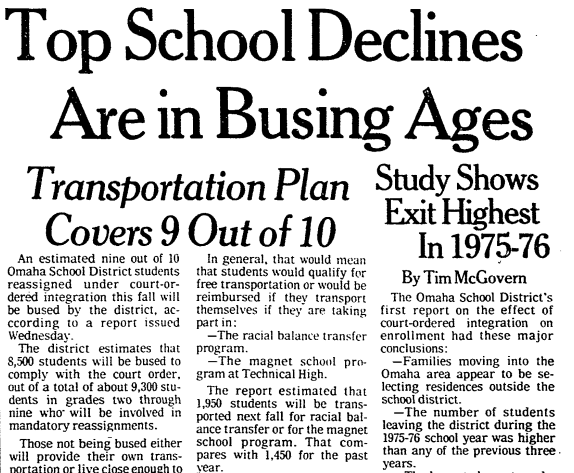

The plan continued to evolve over the summer of 1976, detailing that 8,500 of the 9,300 students reassigned in grades 2 – 9 would be eligible for busing. High school students would be eligible for travel reimbursement if they transferred as part of the racial transfer program or the magnet school program at the Technical High School.

Omaha World-Herald, June 23, 1976

As the new school year approached, schools planned activities to help familiarize students and ease concerns. Elementary schools held open houses, ran pen-pal programs to introduce students, made calendars, and planned opening day events. Institutions also held ride-alongs to allow parents the opportunity to participate in the same bus routes as their children.

Despite all the preparation, no one knew what to expect. While the plan was in place, there was no telling what would come that first day of school or the subsequent months.

Any remaining concerns were left to chance.

Part 2 discusses the plan’s implementation, the return of students, reactions, and results.

(Posted February 24, 2022)

Sources:

- Omaha School District vs US District Court memorandum 10.15.1974

- Omaha World-Herald 6.13.1975 “Orders for Integration Jolt Omaha Officials”

- Omaha World-Herald 12.15.1975 “The Desegregation Plan”

- Omaha World-Herald 1.30.1976 “Emphasizing Racial Differences”

- Omaha Star 1.8.1976 “Chambers Terms Zorinsky Remarks ‘Appalling’”

- Omaha World-Herald 2.8.1976 “Whites to ‘Wait and See’”

- Omaha World-Herald 2.15.1976 “Let Other School Districts Help”

- Omaha World-Herald 6.17.1976 “Court Gets Appeal of Black Parents”

- Omaha World-Herald 6.23.1976 “Top School Declines Are in Busing Ages”

- Omaha World-Herald 8.11.1976 “Peaceful Integration Goal of Cluster Six”

- Omaha World-Herald 8.26.1976 “Statements from Public Officials”

- Omaha World-Herald 8.30.1976 “Parent Ride-Along Turnout Good”