In an earlier post we looked at how a 1975 court order addressed Omaha Public Schools’ racial imbalance by requiring the reassignment of students to new schools and bus routes. Today we’ll look at what happened when the busing plan took effect.

By Breanna Fanta, Editorial Assistant

In an earlier post we looked at how a 1975 court order addressed Omaha Public Schools’ racial imbalance by requiring the reassignment of students to new schools and bus routes. Today we’ll look at what happened when the busing plan took effect.

The nation watched as many cities who received similar court orders responded with demonstrations and violence. This left Omaha residents uneasy about local reactions to their own integration.

As the public waited with nervous anticipation, the district prepared for all possibilities. Teachers willingly participated in training workshops and took on new teaching assignments. Schools prepped for incoming students. Law enforcement officers were placed on standby, monitoring buses and schools to assist with any conflicts.

Omaha World-Herald, Sept. 7, 1976

By the fall of 1976, 150 teachers were reassigned; 1,400 high school students voluntarily transferred; and 9,344 students were reassigned, 60 percent of which were White.

As school year neared, people seemed more accepting of the court order’s terms. A former city-wide PTA president explained that people seemed more willing to comply and help rather than fight it.

“All I have heard would indicate that people have accepted it (busing) as a reality and that they care enough about the kids, whether they’re parents or others in the community, they are determined to make it go well for the kids.”

On September 7, the plan was put to action.

Bus drivers rose before sunrise and arrived at the service lot. There, buses had final inspections and nervous drivers prepared themselves for the day ahead.

While problems were expected to arise, the Director of Transportation assured the public that everything would be handled and that bus routes were tentative.

The biggest problem was a shortage of drivers. Omaha’s busing company struggled to maintain employees and license new drivers. Of the 170 bus drivers needed, only 108 positions were filled. As a result, 2,400 students were not transported to school on the first day.

The only problem for buses in operation was late starts due to the unfamiliarity of routes, student mix-ups, long loading/unloading periods, and pick-up/drop-off location confusion.

“Overall, we didn’t experience any real problems. As far as the desegregation routes go, it (the first morning operations) seemed to have gone fairly smooth,” the Director of Transportation said.

Superintendent Owen Knutzen, who waited with students and helped guide them to the buses, shared confidence in the busing: “This whole thing is going to work fine after the system has been working a while.”

Once students arrived to their assigned school, they joined their peers and were directed toward their classrooms.

Several administrators and teachers expressed satisfaction with the turnout.

A teacher from the Martin Luther King School said that in their 30 years of teaching, they had never seen students start school with a better attitude. The principal of Gilder and Giles shared a similar experience: “It has been the smoothest opening day I have experienced in 24 years.”

Omaha World-Herald, Sept. 8, 1976

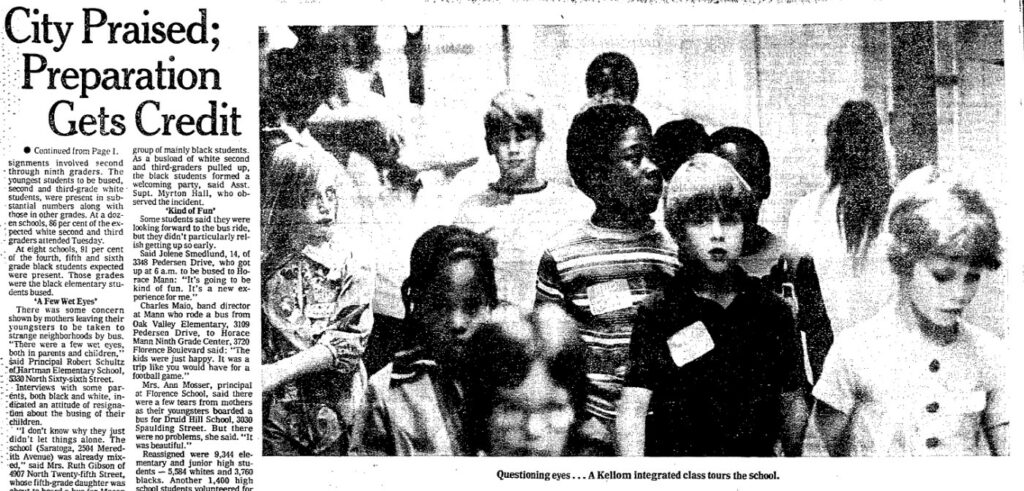

Students shared feelings of excitement and fear, but ultimately demonstrated inclusivity.

Children were reported helping each other, laughing on the playground, and talking over lunch about their summer breaks.

One student expressed excitement about the integration plan because it provided a new experience; another was anxious to meet her pen-pal with whom she exchanged poetry.

A Mason School sixth grader who was concerned about being the only Black boy in his class was later spotted handing out class material, apparently fitting in, and a late bus of White children was cheerfully greeted by a group of Black children.

At the end of the day, one Giles teacher asked her Black students how their day would’ve been different had they attended their old school and “they couldn’t think of a thing.”

Omaha World-Herald, Sept. 7, 1976

While the integration appeared to have gone well, some students did admit frustration with attending an older school with lower quality facilities. “One boy in particular thought Giles was something of a ‘dump.’ But at the end of the day he smiled and told me ‘I’ll be coming back,” a fourth-grade Giles teacher said.

Knutzen, like many others, considered the first day a success and thought Omaha was more receptive to the integration compared to other cities.

“The court-ordered mandate has been carried out by this community in a way which makes Omaha and its people a model for the rest of the nation.”

However, after the first week back, statistics revealed a decline in student attendance and enrollment.

Comparing the first two days of the school year to years previous, it was found that 1 in every 24 students was linked to white flight. On average, there was a decline in enrollment by about 3,700 students the first two days of school. When eliminating factors such as the drop in birth rates, about 2,400 of those were attributed to white flight.

A member of the Northwest Parents Athletic Club felt that by updating facilities, the district would be able to hold on to more students and fight the flight. “We are competing in the market now to keep people in Omaha,” but suburban schools with better facilities were attracting attention.

Conversations continued about ways to combat white flight and the public fought the city bus service on providing proper transportation.

The busing measure remained in effect until 1999, when it ended as part of a voter-approved $254 million bond issue to renovate 24 schools and build three new ones. By the early 2000s community members noticed that Omaha schools were becoming re-segregated and that white flight to suburban school districts was continuing. A 2019 report, available via the University of Nebraska Omaha’s Center for Public Affairs Research, shows Omaha schools as being more segregated than most of the 242 cities included in the study.

Sources:

- Omaha World-Herald 9.5.1976 “Pains Taken in Picking Bus Routes”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.7.1976 “City Praised; Preparation Gets Credit”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.7.1976 “On Bus 150: Mostly Chatter”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.7.1976 “Paid Rides Are Called Off”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.7.1976 “Omaha Has New Busing Angle: School Attendance Near Normal”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.8.1976 “1st-Day Roll Encouraging To Knutzen”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.8.1976 “Preparation, Prayer-and Kickball-Make a Good Day”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.9.1976 “1 of 24 Students Linked to ‘Flight’”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.12.1976 “Open Letter to Omaha”

- Omaha World-Herald 9.21.1976 “Busing Firm Told To Get Into Gear”

- Omaha World-Herald 12.7.1976 “Suburbs Beckon”