In 1877 Thomas A. Edison invented a machine that could record and reproduce the human voice using a tinfoil-covered cylinder. Edison’s phonograph, his trade name for his device, was followed in 1886 by Alexander Graham Bell’s graphophone that used wax cylinders. The possible use of such devices as business machines, and the effect this might have on stenographers, was widely debated during the latter 1880s and 1890s.

The Omaha Daily Bee on February 23, 1890, discussed “The New Talking Machine” and asked, “Will It Force the Stenographer to the Wall?” Promoters of the machines believed that such a result was inevitable, but “knights of the shorthand” thought otherwise. The Bee said: “In view of the great interest which this subject has excited among the short hand writers and the public in general, a number of opinions were obtained from parties interested in the matter bearing upon both sides of the question.”

Stenographer C. A. Potter wasn’t alarmed over the prospect of being replaced by a machine. “It may interfere with our work in a measure in time,” he said, “but it will never knock us out.” H. M. Waring, another of the craft, said that he didn’t think the phonograph could ever replace the stenographer in the nation’s courts. T. P. Wilson added: “Even if the instrument was absolutely perfect in taking a conversation and reproducing it, it could not equal an expert stenographer.” Wilson noted that another disadvantage of the phonograph was a growing belief that it caused deafness.

Promoters of the new machines had a different opinion, however. “At E. A. Benson’s office, the headquarters of the local phonograph company, the [Bee] reporter was informed that in time the stenographer would have to go. ‘Why,’ said the gentleman, ‘with one of our instruments you talk to a little asphaltum cylinder instead of a stenographer and you can talk as fast as you please, with the absolute certainty of your every word being recorded. . . . It never wants an hour for luncheon, never has the grippe, never gets tired, never sleeps, but is always ready to serve you.'”

Asked to list the phonograph’s possible uses, Benson theorized that lawyers could use it to preserve copies of legal documents and that doctors could record instructions to patients on a phonograph cylinder. He said: “The phonograph will also record the beating of the heart, as well as distinguish between the breathing of a healthful person and an invalid, and thus it will enable a person living here or anywhere to be treated by any celebrated specialist in New York, Boston, or anywhere abroad, by means of this little cylinder. You see we mall them, enclosed in a strong wooden box or mailing tube, to any point of the country, and they can be used in any machine.”

Despite such rosy predictions, neither graphophones nor phonographs sold well for office use in the late 1880s and early 1890s. A cylinder could hold only a few minutes of recorded speech, and the machines were expensive. Stenographers managed to hang onto their jobs for decades until modern recording devices and business technology made shorthand obsolete.

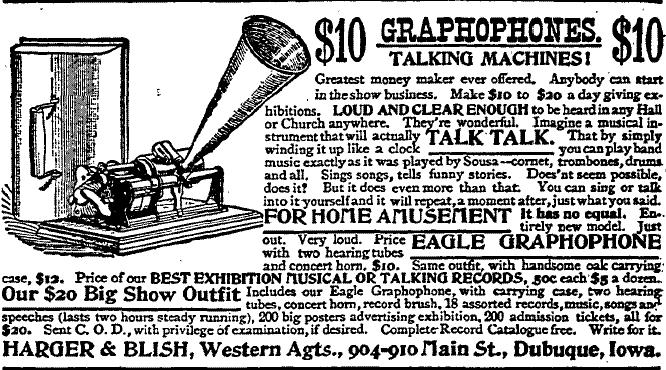

This advertisement for the graphophone appeared in the Kearney Daily Hub on September 26, 1898.