Henry Olerich (1851-1927), a little-known utopian writer, saw his most famous book, A Cityless and Countryless World, published in 1893. It advocated the redistribution of population into planned communities of about one thousand people each as the solution to many rural and urban problems. Olerich was also the author of other utopian works, written during his residence in Omaha from 1902 to 1927.

Born in Wisconsin in 1851, Olerich later moved with his family to Iowa, where he eventually held various school posts. In 1875, at the age of twenty-four, he began a period of self education, during which he developed and first expressed his reform views: government ownership and operation of railroads, the telegraph, and public utilities; woman’s suffrage; the eight-hour day; spelling and dress revisions; direct democracy; and vegetarianism. He and his wife in October of 1897 adopted a baby girl, Viola, so that Olerich could demonstrate how a child should be educated. Disgusted with contemporary educational philosophies, he left the classroom in 1902.

He also moved to Omaha in 1902 and secured a job as a drill press operator for the Union Pacific Railroad. After his retirement in 1910 he designed and patented the Olerich All-Purpose Tractor. Olerich also spent much of his time reading and visiting with a small group of friends who shared his philosophical interests. He never sought public office or campaigned for candidates sympathetic to his views, believing that the utopian novel and essay were better vehicles for promoting social change.

Shortly before the publication of Modern Paradise in 1915, his first utopian piece since A Cityless and Countryless World in 1893, Olerich proposed the creation of a utopian colony on a five-thousand-acre tract in eastern Nebraska. When his “Modern Paradise” was never built, a disappointed Olerich wrote a book with the same name, and eight years later, The Story of the World a Thousand Years Hence. Both consisted largely of ideas found in A Cityless and Countryless World. Olerich’s final effort at describing the ideal society came in 1927 with the publication of The New Life and Future Mating, in which he advocated more rights for women, publicly supported daycare centers, and the concept of “trial or ‘companionate’ mating.”

In 1927 suicide ended Olerich’s career. Although society did not accept some of his ideas, many others, such as woman’s suffrage, eight-hour working days, and direct democracy, have been achieved. He is important not for the style or merit of his writings, but because they illustrate the attitudes and ideas of utopian reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Summer 1975 issue of Nebraska History magazine includes an article on Olerich’s life and work.

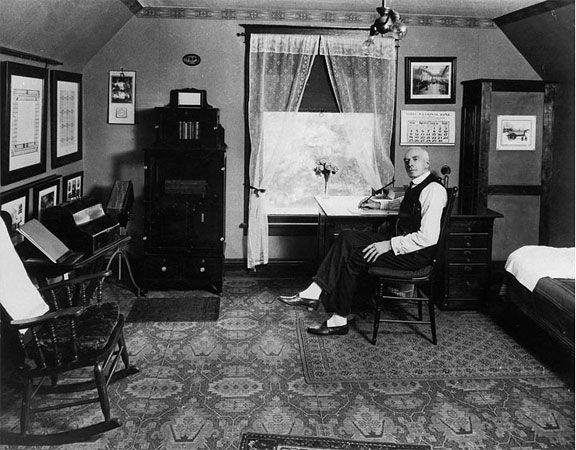

Henry Olerich in his Omaha apartment in 1921. NSHS RG1078.PH2