Today many Nebraskans live in counties known by different names than they were during Nebraska’s territorial years. The first eight counties in the state were Douglas, Cass, Dodge, Washington, Richardson, Burt, Forney, and Pierce, all named for prominent political leaders. Six of these names remained unchanged, but Forney became Nemaha County, and Pierce became Otoe County. In 1855, five counties which no longer exist were set up: Greene, McNeale, Jackson, Izard, and Blackbird. Later Nebraska had a Calhoun County, a L’eau Qui Court County, and a Shorter County.

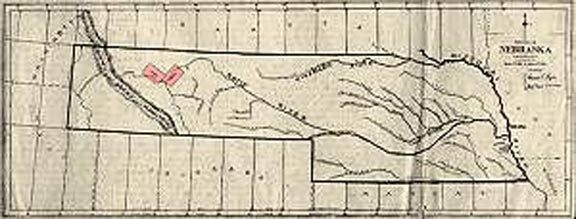

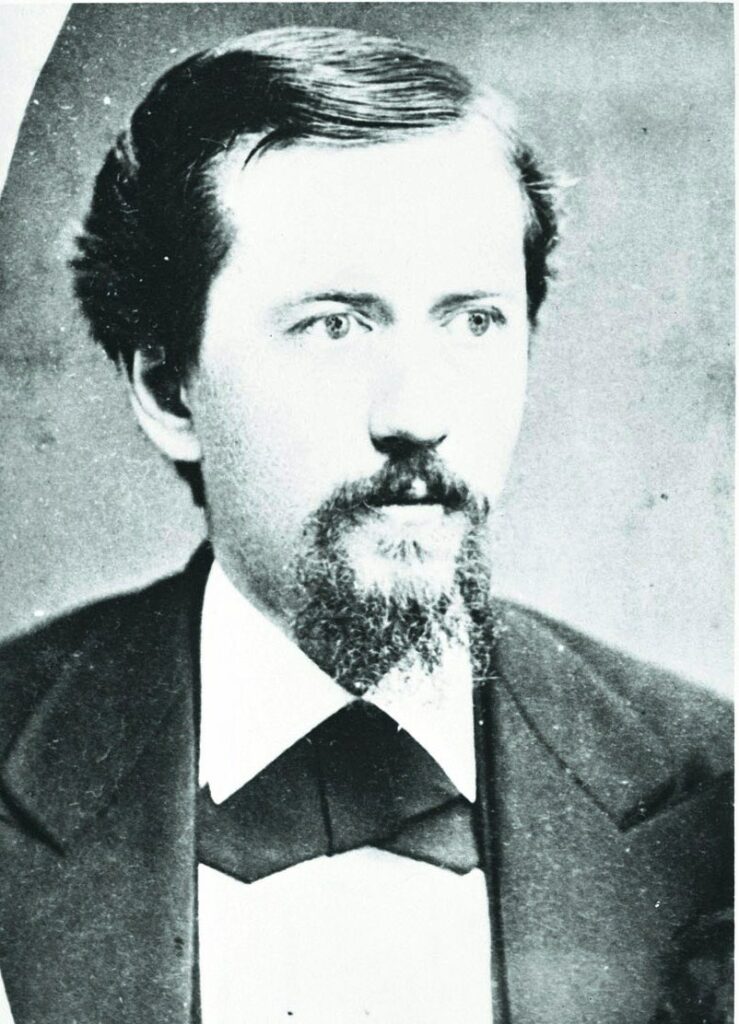

Two other long-forgotten counties dating to territorial days were Morton and Wilson, created by act of the territorial legislature and approved January 6, 1860. Morton County was named for J. Sterling Morton, then territorial secretary; Wilson was named after a land office official. “At that time,” said the Lincoln Evening News in a January 25, 1903, review of the counties’ history, “Nebraska [Territory] included all the territory north of Kansas between the Missouri river and the Rocky mountains, extending to the British possessions. The western boundary began at the northwest corner of Kansas and extended northwestwardly along the summit of the Rockies to the British line.”

The News said that the two counties were located about 200 miles northwest of Fort Laramie, now in the state of Wyoming, “and it is intimated that their formation was due to the ambitious projects of railroad promoters. In the legislative act the boundary of Morton county is given as follows: commencing at a point fifteen miles up the A-la-Prelle river, emptying into the North Platte river from the south; hence in a northerly direction down the A-la-Prelle river to its mouth across the North Platte and to a point fifteen miles in a northerly direction from the North Platte; thence fifty miles in a westerly direction to the Sweet Water river to a point fifteen miles from where the Sweet Water river empties into the North Platte river, thence in a southerly direction down the Sweet Water river, crossing the North Platte, to a point fifteen miles from the North Platte in a southerly direction and from thence fifty miles east to the place of beginning.”

Morton County, on paper at least, was thirty miles wide and fifty miles long. “Wilson county lay half north of the western extremity of Morton county and half still farther west. It was exactly the same dimensions, . . . It extended to within probably a hundred miles of the summit of the Rocky mountains.

“The laws creating these two counties made it the duty of the governor to appoint three commissioners for each county, residents thereof, to call elections on the first Tuesday in June 1860, for the election of the several county officers for each. It required that ten days notice should be given of the election, the notice to be in writing and posted up in three public places in each precinct. Each commission was authorized to canvass the vote, issue certificate of elections to the successful candidates and accept bonds therefrom. The seat of government of Morton county was indicated as Platte City, but the law creating Wilson county specified no county seat.”

The News noted that Morton and Wilson counties apparently never organized, due perhaps to their proposed location several hundred miles from any of the then existing organized counties in Nebraska Territory.

Nebraska Territory, 1861. Rectangular outlines in the extended Panhandle indicate the proposed locations of Morton and Wilson counties. From www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~neycha/

J. Sterling Morton, for whom Morton County was named, about 1859. NSHS RG1013.PH1-6