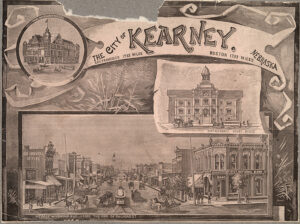

Kearney was booming in 1889 when city boosters commissioned a promotional book entitled The City of Kearney, Nebraska. A copy of this boastful, lavishly illustrated book is in History Nebraska’s collections.

Divided into brief sections, the book covers topics such as “Why Kearney Must Become a Railroad Center,” “Why Kearney Will Be a Large Manufacturing Center,” “Why Kearney Will Become a Second Minneapolis,” and others. Most pages also feature beautiful engravings of local scenes.

Kearney was serious, just as local resident Moses Sydenham had been in 1870 when he tried to convince the federal government to relocate the US capital to Kearney. But now Kearney was in the midst of a water-powered real estate boom. The new Kearney canal promised direct water power and hydroelectric power to manufacturers.

Kearney introduced the first electric streetcars west of the Missouri River, and got into the textile business by opening a cotton mill in 1892.

A local resident named Maud Marston Burrows described the Kearney real estate boom in a 1937 speech for the Nebraska State Historical Society (today’s History Nebraska). She remembered that the city had “an oatmeal mill, a cracker factory, a woolen mill, a candy factory, a bicycle factory that turned out an excellent wheel.” (The high-wheel bicycles of the day were often simply called “wheels.”)

Work began on a railroad from Kearney to the Black Hills. It got as far as the Custer County town of Callaway before the boom collapsed following a nationwide financial crisis and the beginning of a prolonged drought. Burrows said that most of the new homes and businesses in Kearney were heavily mortgaged. Many people lost everything.

The city eventually recovered, but never again would local leaders think that Kearney was on its way toward becoming a major city. The City of Kearney, Nebraska documents the high-water mark of local ambitions.

A much larger monument to Kearney’s boom years stands on the campus of the University of Nebraska at Kearney. A local architect named George W. Frank was among the city’s biggest boosters. He invested aggressively, but paid the price when the boom ended. He lost much of his fortune, but his grand, red sandstone house remains. One of the first homes west of the Mississippi to be wired for electricity, it is open as the G. W. Frank Museum of History and Culture.

By David L. Bristow, Editor

Posted March 14, 2022.

Is Kearney really 1,733 miles from both Boston and San Francisco? (Look closely at top image.) Well, kind of. Read about it in “1,733 Miles from Where? Kearney, Nebraska’s 1733 Identity.”